Welcome readers,

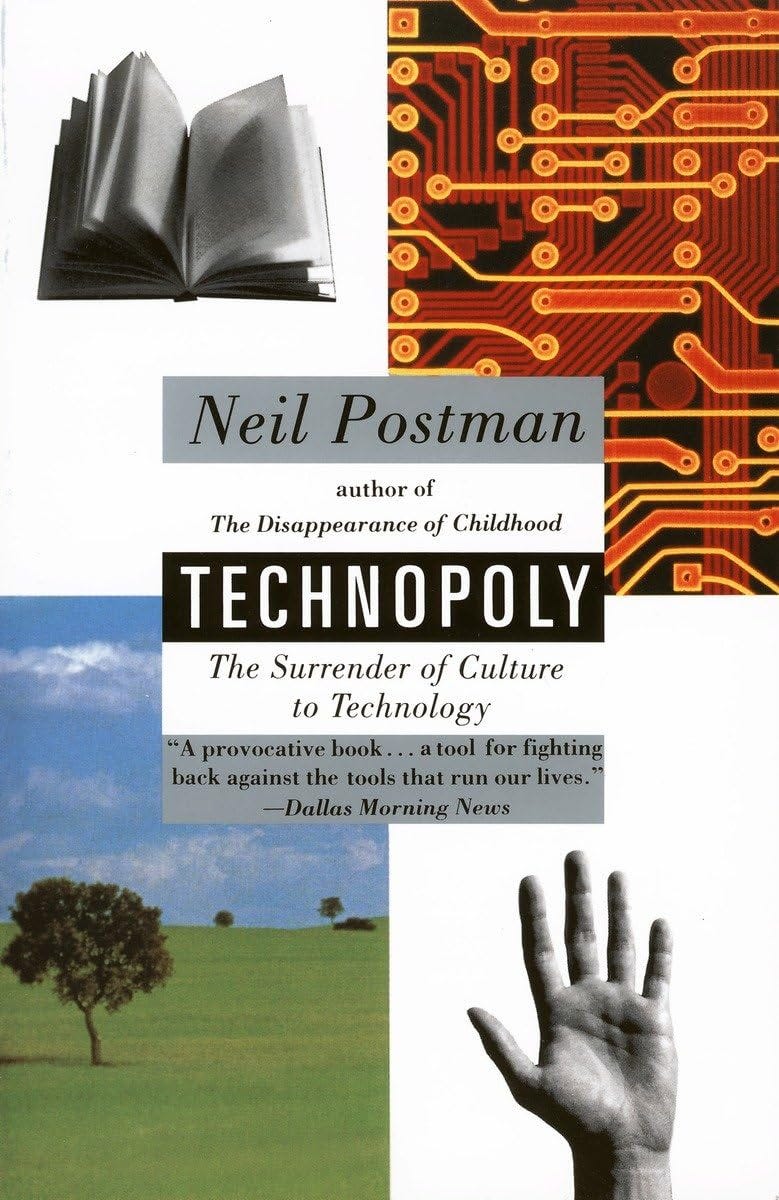

This post comes a little later than I wanted it to. I had intended for it to coincide with the spring release of Technopoly in paperback in 1993. All the same, there is little danger of Postman’s message losing its relevance anytime soon.

Thank you for reading.

In Plato’s dialogue Phaedrus, Socrates relates a tale to his young interlocutor for whom the dialogue is named. In it, the Egyptian King Thamus chastises the naiveté of the god Theuth, who has come before his royal audience seeking the general dissemination throughout Egypt of his new inventions: “He it was”, Socrates tells Phaedrus, “that invented number and calculation, geometry and astronomy, not to speak of draughts and dice, and above all, writing”.1 While Thamus speculates about the benefits and drawbacks of each invention for use by his people, Theuth boasts above all about the usefulness of the last of these, bragging that “Here, O king, is a branch of learning that will make the people of Egypt wiser and improve their memories; my discovery provides a recipe for memory and wisdom.”2 In Thamus’ reply to these assurances we encounter an important idea: “‘O man full of arts”, he admonishes the proud god, “to one it is given to create the things of art, and to another to judge what measure of harm and of profit they have for those that shall employ them”.3

I will save for later the specifics of Plato’s famous critique of writing which follows, but the point which concerns us here is this: it makes little sense to assume that those with cleverness enough to invent new crafts also possess wisdom enough to judge their appropriate implementation or predict the course of the cultural change they will initiate. As far as Thamus is concerned, though the god may have the power to bring the art of writing into being, it is for the political decision maker—the wise King to whom is entrusted the political and social well-being of his country—to assess their suitability for the life of his people.

It is with this parable, and with this lesson, that Neil Postman begins his book Technopoly—an ironic vessel, as was Plato’s own dialogue, to come bearing a warning about the technology of writing—which was released in paperback by Vintage Books thirty years ago in the spring of 1993. Unlike Thamus, whose mistrust is directed specifically at the technology of writing, Postman does not recount this admonition in order to warn of the effects of any particular technology, but to teach a lesson about all technologies and their interaction with the cultures that adopt them.

From our vantage point, we might say that Theuth represents a characteristically modern enthusiasm for, and Thamus a largely premodern mistrust of, the socially destabilizing influence of innovation in its many forms. Postman asks us to take seriously the judgment of Thamus, which teaches that the technological cunning of the clever god should not substitute for the political sagacity of the wise king. The broader lesson, of course, and the lesson Postman wishes his readers to hear, is that those who are responsible for developing a new technology are the last people who are in a position to decide what its practical effects will be, let alone whether those effects would be in the best interests of the political community.

But this, in effect, is the situation we have today: the developers of new technologies release them at will into the world, and the rest of us, whether eagerly or with trepidation, must learn to assimilate them into the fabric of our lives, and our culture and politics must do their best to brace themselves against the shocks—whether they were foreseen or not—that inevitably result. We might say that modernity has done remarkably well at doing just that; we have always adapted, at least eventually, to the reconfigurations that follow from technological change and have never failed to emerge better off. But Postman, perhaps like Thamus, suggests that we might benefit from something resembling a cultural immune system, a vigilant defensive reflex wielding an informed skepticism and made possible by the right sort of education, to establish a barrier—or at least to introduce some friction—between new technologies and the culture to which they seek access. Both are suspicious, in other words, of the idea that is so popular today among the advocates of social disruption, that technological innovation has only upsides, and that exhortations to think of downsides are unworthy of consideration.

The world in which Neil Postman drew his last breath in October of 2003 had only just witnessed the stunning rise of an internet that was by then accessible to the ordinary person, and social media not at all. Facebook would be founded the following year. While decades-old cultural criticism is typically best read as a kind of time capsule, capturing a particular moment’s anxieties and preoccupations which would soon be made to look ridiculous by the ineluctable passage of time, Postman’s observations in books like Technopoly and Amusing Ourselves to Death (1985)—which is concerned mainly with the medium of television—have the uncommon, if dubious, distinction of having aged so well that they bear a message that is more urgent today than it was during his own lifetime. Uncommon, because, unlike most books of their genre and vintage, they can still be profitably read for guidance in a world facing perplexities of which Postman never knew. Dubious, because their continued relevance would not be welcome news for Postman himself, suggesting as it does that the technological trends that so worried him have only been exacerbated by the intervening decades.

With a scolding yet witty prose that still speaks powerfully to partisans of both the left and right, Postman may be seen as a Cassandra-like figure whose warnings were dismissed by the culture at large, despite what proved to be their increasing plausibility in the years that followed (one early review described Technopoly as “strident, even paranoid”).4 Hindsight has come to see Postman—to borrow another figure from ancient literature—as a sort of dark inversion of St. John the Baptist, presaging the coming age of reality television and social media, shouting in the wilderness about all that these new forms of media held in store for our politics, culture, and lives.

Amidst the revival of interest in Postman’s books in the last decade, the influence of Amusing Ourselves to Death has been felt more deeply than that of Technopoly. Starting around 2016, many on the left were quick to perceive a common thread linking television’s influence on politics and culture from the 1960s onwards to the smartphones and the social media that beamed out of them beginning in the 2010s. The outcome of that year’s presidential election seemed to be the embodiment of everything that was wrong with the two media technologies that had made it possible: television (Trump first projected his gilded image as a decisive, hard-bitten businessman to a national audience on The Apprentice) and Twitter. As Ezra Klein, writing for The New York Times, has remarked of Amusing Ourselves to Death, Postman saw that, beginning with television, “[t]he border between entertainment and everything else was blurring, and entertainers would be the only ones able to fulfill our expectations for politicians.”5

Those on the right, who in recent years have cast an increasingly suspicious eye towards the power and influence of technology companies whose values they deplore, have also found common cause with Postman. For some of them, his warnings are realized not by a single entertainer-turned-political-incendiary, nor even as the general derangement of serious politics into farcical entertainment, but rather in the form of a cadre of powerful and unaccountable private companies that are committed to smothering disfavored (i.e., conservative) viewpoints. According to this view, a theory of the public sphere that authorizes the private companies that control the means of communication also to govern which perspectives will and will not be heard raises structural concerns that require a deep reappraisal of the technological system making such a situation possible. Then there is the group of conservative Christians who have taken what they call the “Postman Pledge”, a fusion of Postman’s ideas with standard Evangelical platitudes, vowing, among other things, to keep their children off smartphones and social media for a period of one year, as if Postman himself ever made such a stark recommendation (which, for the record, he didn’t).6

But it is traditionally-minded conservatives, who worry about cultural stability and the thoughtless discarding of older and more time-tested ways of life, who have the strongest basis in Postman’s work. Although throughout his writing Postman was usually quite guarded about the specifics of his own religious and political views, the temperament, if not the politics, of his work is fundamentally and unmistakably conservative: in our technophilic culture, he writes in Technopoly, we “see only what new technologies can do and are incapable of imagining what they will undo.”7 His point here, of course, is not that the existing culture is faultless and that any change would therefore be a corruption of its perfection, but only that the denizens of a technopoly, if they value anything enough to want to keep it, ought to recognize that the ideology that governs them is at war with whatever of permanence they might wish to preserve. Put another way, to the extent that we recognize technopoly as the dominant mechanism behind the major decisions, public as well as private, that shape our collective life, we have no right to wonder why our world is so perpetually addled and destabilized.

Technopoly represents a broadening of Postman’s scope from the effects of television in particular to the modern world’s total embrace of technology more generally. He defines technopoly as “a state of culture” that “consists in the deification of technology, which means that the culture seeks its authorization in technology, finds its satisfactions in technology, and takes its orders from technology.”8 In other words, in response to the most serious questions human beings have asked—where should I place my trust? how should I live my life? how should we be governed?—the same answer always comes back: look to technology. (This view is espoused with unusual candor by Australian philosopher David Chalmers in his recent book, Reality+, which defends the authority and centrality of modern and futuristic technology in thinking about the timeless questions of metaphysics, epistemology and ethics.9) Of course, this comprises everything from the trivial fact of our finding entertainment in video games to the much more consequential technocratic view that the levers of politics and society are best manipulated by social-scientific theories informed by huge amounts of data. Their common denominator is that technology alone—having displaced, for better or worse, older sources of guidance—has the authority and credibility to minister to all our needs.

“Those who feel most comfortable in Technopoly”, Postman continues, “are those who are convinced that technical progress is humanity’s supreme achievement and the instrument by which our most profound dilemmas may be solved.”10 According to the technophiles, whatever challenges a new technology may present, its solution always lies in yet another technological innovation. That is, not only are all first-order problems solved technologically, the very problems that attend technology itself must also be solved technologically. And the logic of this upward spiral of technical problem-solving further corroborates to its acolytes the idea that technological change is fundamentally additive, justly claiming for itself the mantle of progress. Perhaps the most striking case of this in recent times has been the assurances of OpenAI CEO Sam Altman that concerns about alignment and interpretability in modern AI systems will ultimately be solved not by the researchers and engineers responsible for developing the technology, but by AI itself. That is, these problems will be solved not by human engineers, but by near-term developments in the very technology that is the source of the worry—a consolation that is only available if we double down and commit to its further development. The company wrote in a blog post released last year: “our AI systems can take over more and more of our alignment work and ultimately conceive, implement, study, and develop better alignment techniques than we have now.”11

Postman challenges this idea in an important passage that echoes the first of Melvin Kranzberg’s famous six laws of technology (“Technology is neither good nor bad; nor is it neutral”12) and which captures much about Postman’s view of the dynamics of the technological world:

Technological change is neither additive nor subtractive. It is ecological. I mean “ecological” in the same sense as the word is used by environmental scientists. One significant change generates total change. If you remove the caterpillars from a given habitat, you are not left with the same environment minus caterpillars: you have a new environment, and you have reconstituted the conditions of survival; the same is true if you add caterpillars to an environment that has had none. This is how the ecology of media works as well. A new technology does not add or subtract something. It changes everything. In the year 1500, fifty years after the printing press was invented, we did not have old Europe plus the printing press. We had a different Europe.13

Here, “total change” means that the changes within the cultural ecosystem that are set in motion by the introduction of new technical artifacts never remain exclusively tied to those artifacts alone; they reshape everything within that cultural environment. The metaphor of the technological ecosystem, which is of course deeply indebted to earlier work by Marshall McLuhan and others, was central for Postman, who founded the program for Media Ecology (now Media, Culture, and Communication) at NYU in 1971. In the last decade, many have recognized that our technological and media landscape has again changed ecologically, in Postman’s sense of the word; our recent experience of the rise of the smartphone and social media provides another case study in this phenomenon which may prove equally decisive but which is occurring much more quickly than the centuries that were required for the most momentous effects of the printing press to be fully felt. Few would argue that today we are living in the old world plus smartphones; we are living, surely, in a different world. Widespread and daily experience tells us that something about the very conditions of existence have changed profoundly, not just the artifacts that furnish daily life.

While these changes have manifested in far-reaching ways affecting how we relate to each other (just ask, say, anyone who is single and looking for a date), Postman thought that the power of technologies to structure experience runs deeper still, shaping so intimate a part of life as language itself: and here we return to Plato’s Phaedrus, which has still to teach us another lesson about technology. Socrates worries that Theuth’s prized art of writing not only has the ironic effect of undermining the memory—precisely the faculty it was devised to support—but also that it loosens our precious grip on reality. When we write, he argues, the meaning of living speech—which originates within the speaker and responds understandingly to those who question it—is fixed in place by “external marks”.14 When these marks are affixed only to surfaces, knowledge of their meaning and significance ceases to be securely stowed in the minds of those who know and becomes vulnerable to the capricious changes of the broader technological and cultural ecology. That is, in another ironic reversal, by disburderning the mind of what it ought to know and possess, the written word alienates knower from known and makes possible a dangerous fragility within the universe of meaning.

Postman’s observations about changes in all media technologies strike a similar note:

Writing changed what we once meant by “truth” and “law”; printing changed them again, and now television and the computer change them once more. Such changes occur quickly, surely, and, in a sense, silently. Lexicographers hold no plebiscites on the matter. No manuals are written to explain what is happening, and the schools are oblivious to it. The old words still look the same, are still used in the same kinds of sentences. But they do not have the same meanings. And this is what Thamus wishes to teach us—that technology imperiously commandeers our most important terminology. It redefines “freedom,” “truth,” “intelligence,” “fact,” “wisdom,” “memory,” “history”—all the words we live by. And it does not pause to tell us. And we do not pause to ask.15

Postman is not here recommending that we return to an oral culture—or even that we bar our children from using the technology of writing for the next year, as some have interpreted his message. But if we are inclined to respond with a roll of the eyes to the apparent paranoia underlying Postman’s consternation about the destabilizing effects of novel technologies on our language, we should consider some perhaps less weighty but more commonplace examples of this phenomenon since Postman wrote these words. How, we might ask, have the meanings of words like “friend” or “community” changed in the last ten years alone? Or, perhaps more significantly, how has the word “intelligence”—already largely an invention of modern psychologists—again changed in the age of machine learning? These experiences counsel that we should also expect that our concept of “creativity” will undergo—is already undergoing—a similar retooling in the age of AI-generated art and literature; indeed, pressure of a different sort has already been applied to the same word by the recent prominence of content “creators” who now thrive on the possibilities supplied by platforms like YouTube and Instagram. Nobody doubts that all natural languages change over time for reasons having nothing to do with technology, but the close connection between these examples—and many others besides—and concrete changes in the landscape of technological artifacts, calls on thoughtful people to take heed and ask these questions.

That the core of Postman’s social critique—that the enthusiasm for invention, possessing as it does the invisible power to reshape meaning, is dangerously unmoored from social and political judgment—had been captured so accurately in Plato’s dialogue is testament less to Postman’s unoriginality than to the fact that we here find ourselves in the midst of perennial human questions, however little traction they may have in the minds of contemporary techno-optimists. What is novel and compelling about Technopoly is that Postman brings an ancient set of concerns to bear on the urgent questions posed by our uniquely modern predicament. Those who are skeptical that he has anything relevant to say to us who are by now so entrenched—if seldom contentedly—in technopoly should reflect that as of 2023, because of decisions made by none but a tiny number of technologists, it is no longer absurd for the reader to wonder whether these words were written by a human or an AI algorithm trained on billions of lines of existing text. In this lies the prescience and enduring relevance of Postman’s now 30 year-old book.

Plato, Phaedrus, 274c-d

Ibid., 274e

Ibid., 274e-275a

https://www.nytimes.com/1992/03/06/books/books-of-the-times-technology-s-erosion-of-culture.html

https://www.nytimes.com/2022/08/07/opinion/media-message-twitter-instagram.html. For the most recent and exhaustive catalog of examples of this phenomenon, I refer the reader to a recent article by Megan Garber in The Atlantic entitled “We’ve Lost the Plot”.

https://www.theamericanconservative.com/taking-the-postman-pledge/

Postman, Technopoly, 5

Ibid., 71

Chalmers, Reality+, “Introduction: Adventures in Technophilosophy”. For more on the implications of this way of thinking for our common world, see Alexa Hazel’s recent article in The Point, “The Virtual Condition”.

Postman, Technopoly, 71

https://openai.com/blog/our-approach-to-alignment-research

Melvin Kranzberg, “Technology and History: “Kranzberg’s Laws”” in Technology and Culture, Vol. 27, No. 3 (Jul., 1986), pg. 545.

Postman, Technopoly, 18

Op. cit., 275a

Postman, Technopoly, 8-9

I used the introduction to Technolopy with my AI and Ethics class here in a public school, coupled with Noreen Herzfeld's discussion of "Do You Really Need A Body" after watching a Ray Kurtzweil's Singularity Ted Talk with high school seniors. The core question - Are you living in a Technolopy and if you are, what do you think about that?

Provoked thoughtful reflection and decent discussion...because the concept felt both immediately true and a bit overwhelming to most of the students. For anyone not regularly working alongside or teaching 17 and 18 year old students, you should know there is a lament about "brain rot" from social media that is leading more students towards a desire for engaging literature, not just YA titles, but works earlier then 1900, too. These students understand any of these programs are tools first, not immediate progress or quickly implemented human replacements.