Strange Shadows [Part I]

Two centuries of photography have prepared the way for algorithmically-generated images. Now the image-world is becoming a Museum of Babel.

Welcome to Ever Not Quite—essays about technology and humanism. This is the first in a two-part installment, the second of which can be found here.

In this essay, I wanted to think about what it will mean to live among the images created by algorithms—to be awash in them, to have our vision flooded by them—by situating this new class of images within the longer story of technical images in general, and in particular of the nineteenth century’s invention of their elusive antecedent: the photograph. The proposal I want to explore here is that modern algorithmic images—the term I am using for images that have been created by artificial intelligence—are both continuous with but also a departure from the photographic techniques which made them possible in ways that are both direct and incidental. Part I is about photographs. In Part II, I’ll connect what I say here to algorithmic images themselves, which are the endpoint of the story I’m trying to tell, and the reason for telling it in the first place.

Much of this essay owes insights and inspiration to Susan Sontag’s masterly On Photography, a collection of six essays which was published in 1977. Sontag’s writing about photography manages to bring an analytical clarity to her subject, just as it heightens her reader’s sense of its essential intrigue and elusiveness. In a short foreword, Sontag comments that “the more I thought about what photographs are, the more complex and suggestive they became.” This has also been my experience; the more I read and thought about photographs—about images of all kinds—the more mysterious they seemed to me to become, and the stranger it became that we have largely ceased to wonder about them at all. This essay is my attempt to capture some of that mystery.

The Friday after next (October 11th), I’ll put out a curated collection of quotations about photography, images, and the visual sense which have informed the background of this essay and helped to shape the thinking that went into it.

As always, thank you for reading. If you find value in the newsletter, please share it with others—it’s the best way for new readers to discover it.

“I felt dizzy and wept, for my eyes had seen that secret and conjectured object whose name is common to all men but which no man has looked upon—the unimaginable universe.”

Jorge Luis Borges, “The Aleph”

Philosophy since Plato has often compared the reality available to the senses, prior to any creative gesture of the human hand, to a kind of image-world, severed from the unseen truth of things. Knowledge of the true reality is acquired by means of a faculty higher than that by which we take in mere appearances, one which approaches more directly the hidden sources of the images we see. But long before the emergence of anything we might wish to call ‘philosophy’, it must have been understood that appearances may diverge from the real things that cause them: the V-shaped stick protruding from the water, upon extraction, reveals itself to be rather straight; the oasis seen on a summer day’s horizon disappears, seeming to evaporate in proportion to the rate at which it is approached; the startling glimpse of a snake arching at the periphery of our vision is quickly transformed into the more reassuring scene of a rope resting harmlessly on the ground the moment we fix our gaze upon it. Even so, the rupture between things and their appearances must have made a certain sense, because human beings, themselves image-makers, understood that that images possess a peculiar independence, even autonomy, from the reality which they purport to depict; distortions, misdirections, and simplifications of all kinds are simply the terms on which we are granted life among the world’s faithless appearances.

Less immersive than the sense of hearing—so closely affiliated with the intimate supplications that accompany religious conversion, in which the hearer might respond to an auditory ‘call’ from someplace which mysteriously cannot be located—sight is the most analytical of the senses, and thus also the sense which we experience as most akin to knowledge. While a voice is most effective in moving its hearer when it seems to whisper directly into the ear, delivering its message in verbal succession, the eye requires distance, a spatial transparency between itself and the visible scene it beholds, and which it takes in all at once. But wherever knowledge is offered, so too lurks the possibility of deception. This is the game we play with visible things, and the hazard we court in all our dalliances with images.

In a stroke of mythic genius, Plato famously likened our world to a ‘cave’, a kind of prison of mass deception, overseen and manipulated by a parade of what in modern parlance we have come (rather accurately) to call “influencers,” whose mesmeric spectacles take the form of shadows which resemble, imperfectly, their ideal counterparts, which are illuminated by sunlight only beyond the cave’s mouth. Those who would free themselves from their fetters and glimpse the cosmos as it truly is must forsake these shadows, and exchange mere images for things themselves, copies for originals. Images are signposts, perhaps, though little more, which point back towards that other, more real world which they imitate only in rough outline. What Plato did not consider, however, was that our experience of the image-world—the totality of images available to our vision—would prove to be subject to historical processes, and that what it would mean to inhabit a world made up of images might be transformed by innovations in the very nature of the images we see. If the ancient mind learned to distrust images on account of their capacity to deceive, recent history has alerted us to the ways that they are capable of more than simply blurring the line which distinguishes reality from illusion; images give shape to life in ways that may seem almost paradoxical.

In the nineteenth century, something occurred in the adventure of technique that forever changed our relationship with images—and, with it, the very terms of our imprisonment in the Cave: with the development of processes for fixing natural images onto surfaces, the visible world first began to reproduce itself. The autonomy which images had always enjoyed relative to their originals now became radicalized as a new class of images was produced by mechanical means through which images could be separated from things. These images achieved an unprecedented independence from the working hand which had presided over the creation of all prior images. This new universe of mechanical images, which proliferated explosively in the decades following the 1820s, when Joseph Niépce first used bitumen of Judea to permanently affix, if only in the most spectral reports, natural images onto the surface of pewter plates, began to resemble more and more a self-reflecting hall of mirrors: it ceased to be true that images were vessels bearing the vestiges of the human being who had created them, “woven together by the energy of countless judgments.”1 These technical images—soon to take the name “photographs” (from the Greek roots phōtós and graphé, or literally “light-drawing”)—reproduced appearances without any direct intervention by the hand of the craftsperson.

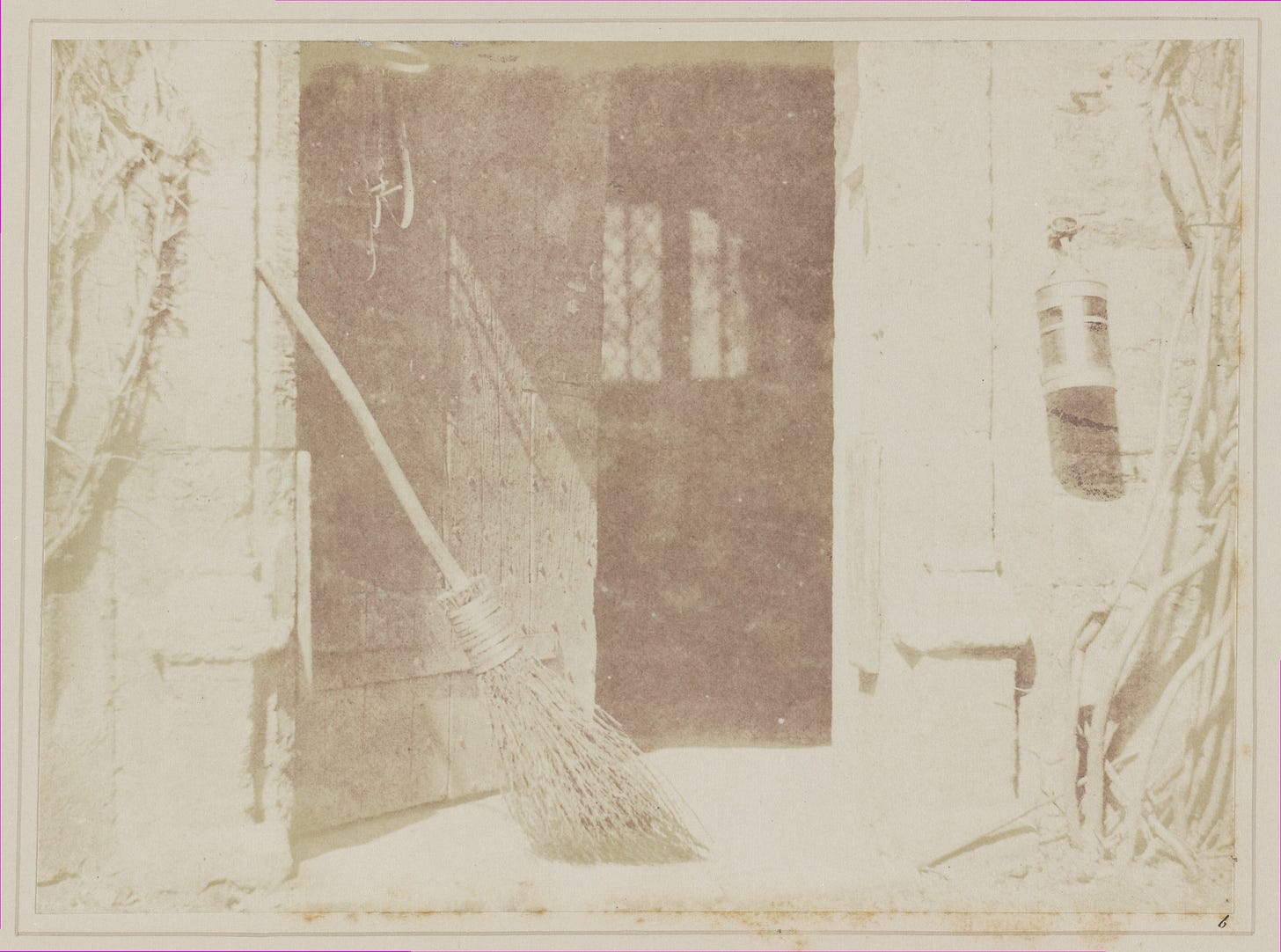

Unlike any image created prior to the 1820s, this new class of images seemed not to depict someone’s interpretation of the world—a product of human deliberation and craftsmanship—but actual traces of it, as natural light deposited itself almost automatically, by means of the optical geometry carefully arranged inside the camera’s dark cabinetry. The early photographer and calotypist William Henry Fox Talbot suggested a metaphor for this new method in the title of his 1844 collection of twenty-four photographic plates, The Pencil of Nature, which he introduced in part with the following remark:

[T]he plates of this work have been obtained by the mere action of Light upon sensitive paper. They have been formed or depicted by optical and chemical means alone, and without the aid of any one acquainted with the art of drawing. It is needless, therefore, to say that they differ in all respects, and as widely as possible, in their origin, from plates of the ordinary kind, which owe their existence to the united skill of the Artist and the Engraver.2

Now nature, by means of its very own optics and chemistry, had found with the aid of human technical ingenuity a capacity to produce images of itself which were as tangible and as lasting as any painting, yet more faithful to appearances than any painting ever could be. In fact, nearly a decade prior to the publication of Fox Talbot’s collection, Louis Daguerre himself had gone to the heart of the matter when he wrote, in an 1836 notice circulated to attract investors to back the new technique for image-creation, that “the daguerreotype is not merely an instrument which serves to draw Nature; on the contrary it is a chemical and physical process which gives her the power to reproduce herself.” In literary terms, the painter’s interpretive translation of the visible gave way to the camera’s direct quotation of it by means of its mechanical operation.3

As the poet Robert Lowell would write a century and a half later, well into the photographic era, “The painter’s vision is not a lens / It trembles to caress the light”.4 No longer did light first need to pass through the sensitive plexus of eye and mind on its way to fixing itself, however transformed, onto a canvas, but now did so almost automatically following the course laid out in advance by natural laws. Images now proliferated which had not been produced by the judgments of any mind, nor by the strokes of any hand, as the mechanical operation of the camera was extended by the complementary processes of mechanical reproduction which subsequently disseminated them, and rendered the optical disclosure of reality a public experience like never before.

Early interpreters of photography often concluded that nature’s power to reproduce its own image by means of the camera introduced a vital objectivity into the universe of images, long the exclusive domain of the subjective vision of individual artists. It was this conviction that led the Hungarian photographer and painter László Moholy-Nagy to set his two vocations into mutual antagonism when he wrote in 1925:

Thus in the photographic camera we have the most reliable aid to a beginning of objective vision. Everyone will be compelled to see that which is optically true, is explicable in its own terms, is objective, before he can arrive at any possible subjective position. This will abolish that pictorial and imaginative association pattern which has remained unsuperseded for centuries and which has been stamped upon our vision by great individual painters.5

Indeed, it wasn’t long after the emergence of the photograph—or, the “photo-document”, as the photographer Berenice Abbott called it—that many noticed that nature’s newfound power of self-duplication by means of the camera could be useful in the investigation of nature itself. The camera became a scientific instrument in its own right, joining the microscope and the telescope, with their long-established ability to enlarge what is small and to draw near what is distant, in rendering nature available for inspection. Apparently free not just of the deficiencies of the eye, but of any interpretative guesswork at all, the camera shows simply what is there.6 By some mechanical prestidigitation, the photograph seemed to take an optical fact—that atomic unit out of which the edifice of scientific knowledge is constructed—and transfigure it into scientific truth.

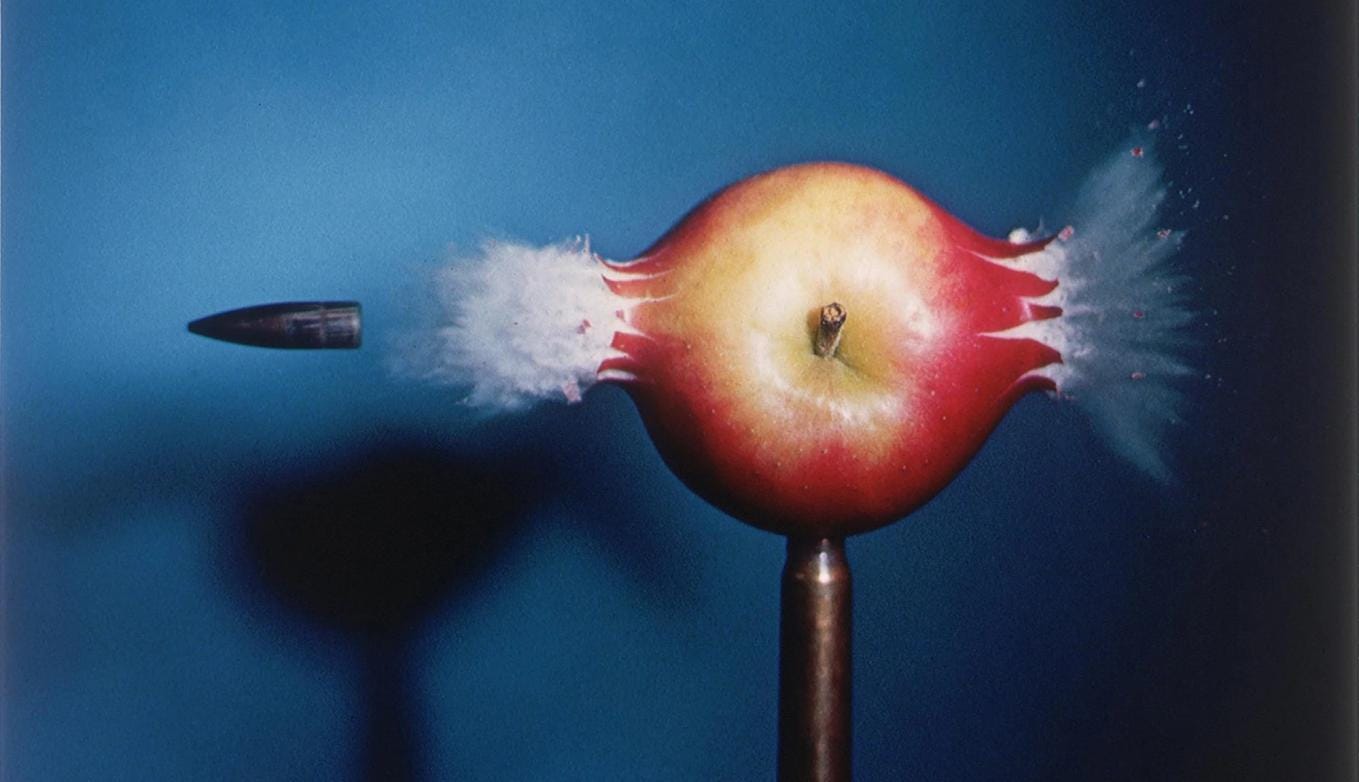

Outside the laboratory, the camera’s inclination to objectify showed what we had always seen, but in ways we had never seen it before; faster shutter speeds and exposure times could bring to a standstill what occurs too quickly for the eye to discern: as a series of cabinet card photographs taken by Eadweard Muybridge in 1878, “The Horse in Motion”, which defined the indistinct blur of the equine gait; or in Harold Edgerton’s 1964 photograph of a .30 caliber bullet explosively exiting the opposite side of an apple, to which he gave the playful title “How to make applesauce”.

As units of visual testimony, photographs manage to convey a sense of objectivity, believability, and authority on the basis of the fact that they are, at least in part, machine creations—and not byproducts of any organic perceptual faculty. Our reflexive presumption of the camera’s objectivity is precisely what has made photographs so useful for the purposes of propagandists and advertisers, who depend on the public’s trust in the reliability of the photographs they are shown. (Even the contemporary internet’s half-serious insistence upon “pics or it didn’t happen” draws on the common assumption of a photograph’s adequacy as a source of proof.) The camera’s ability to furnish a richly detailed visual account also recommended photographs for use by any professional for whom precise information is paramount: surveyors, crime scene investigators, doctors, medical examiners, and even spies. In all such cases, the camera’s greatest virtue is the way that it circumvents the inadvertent prejudices of the senses and of memory, the unreliability of verbal depositions, and the artist’s inclination to beautify.

But in remarkable contrast to its usefulness in professional applications, photography managed eventually to transcend the limitations associated with its status as a mere technical procedure and acceded at last—although not without controversy—to the more prestigious precincts of art. This promotion in the dignity of the photograph rested on all that the mechanisms of the camera could not provide: the photographer’s eye for what a fleeting detail might reveal, for juxtapositions, odd gestures and expressions—even the social graces needed to make a subject comfortable sitting and looking into a camera helped to provide the photographer access to intimate scenes that the camera by itself could not. This is why it can be easy to pick out a photograph you might never have seen from the corpus of the most distinctive photographers—Robert Frank, Edward Weston, Diane Arbus—whose work embodies a unique sensibility for what is worth documenting and how it should be presented. Indeed, photographs, with their selections, omissions, croppings, and recontextualizations are as much interpretations of reality as paintings and drawings are—a truth that the camera’s automatic, optical objectivity tends at first to conceal.

The camera’s proclivity to aestheticize, its use as a tool in the hand of an artist rather than a technician, is connected also to the power of photographs to intensify subjective feelings—nostalgic longings for what is past, desire for what is distant or unobtainable, as inducements to wonder and reverie. The photograph of the lover, longed for but out of reach, kept in a notebook or a locket until the moment of some long-awaited reunion; the images of children guarded in the wallets of their parents, long after the child is grown; the family photo album which puts us into contact with those who live far-away, or, perhaps, the living into contact with the dead: these photographs supply something more than cold documentation of precise information, offering those who possess them a tangible monument which preserves and brings its subject to presence in a way that no other kind of image can. The child may now be grown or the loved one living abroad, but the photograph—now faded perhaps, its edges curling—remains uncorrupted: detailed, faithful, and stenciled off the very light once reflected by the beloved original.

Indeed, in addition to the unique emotional alchemy that can form between a photograph and a particular viewer, photographs themselves cannot help showing the world subjectively, reproducing images of things as they are seen from a particular point of view. Only with great patience had the tradition of European painting mastered the art of providing a viewer the sense of being situated within the three-dimensional space that can be simulated by a flat surface. While medieval paintings once emphasized symbolism, sizing figures according to their allegorical significance, Renaissance painters made use of the geometrical rigors of linear perspective, in which the sizes of things are determined by their distance from the viewer, and so began to depict scenes as they might be regarded from a particular location. Every photograph already shows the world from wherever the camera operator happened to be standing at the time it was taken, and whatever a photographic document may be able to establish about an allegedly ‘objective’ reality, it must always do so from a standpoint conditioned by subjectivity.

Prior to the development of the camera, the memetic arts—some more conspicuously than others—were often vehicles for ideas and narratives contrived explicitly in order to offer viewers some measure of moral or spiritual uplift. Working in the language of color, form, and composition, painting played freely with the poetics of the visually possible, but it also frequently narrated significant cultural or religious stories, and instructed the viewer concerning divinity, or cosmology. This was less true of photographic images, which seemed not to point beyond themselves, but to refer their viewer directly back to the surfaces that had created them: an anonymous rooftop in eastern France, a wooden door opening onto a dark interior, a man’s hapless leap into a shallowly flooded station yard. Indeed, many of the earliest photographs drew deliberately on the manner of observation characteristic of those paintings which were least inclined to grand narratives and symbolism: the landscape and the still life. These were scenes taken directly from things as they are, and the artist was less interested in communicating a message than in the exercise simply of seeing the world.

Photographs of course are also capable of conveying lofty messages, but they accomplish this in an altogether different way than paintings do. In contrast with a painting, in which every line and stroke is a deliberate decision of the painter (overlooking here the more frenetic productions of abstract expressionism), a photograph gathers precious little of the photographer’s intentionality. Painters and photographers both select from reality, omitting much of what offers itself. The painter excludes details—handmade images do not reproduce reality down to its smallest feature. The distinctive dimension of the photographer on the other hand is temporal—the camera declines invitations to capture everything that occurs before its lens, choosing to immortalize only a single moment that has been recognized to bear special significance. When we wonder about what is going on in a particularly captivating photograph, this is often what we are asking: what might have preceded and what could have followed this particular moment in time? What is the larger story within which this is but a single instant?

The fact that photographs are so often captioned—that is, aided in their work of situating themselves in time or in history by the altogether different medium of language—reveals their relative weakness in capturing and communicating any particular meaning on their own terms. Whatever an uncaptioned photograph can be said to mean—and what gives great photographs a sense of expansiveness—can only emerge out of the bare facticity of what the camera has captured. Meaning begins with the tacit statement that the photographer has found something in the course of actual events which deserves to be preserved. As if speaking to us through the photograph, the photographer tells us: “I have decided that seeing this is worth recording”.7 The photograph extends the human capacity for observation and renders it self-conscious: not only does its subject show itself, but in showing itself, it is asked also to explain what is interesting about it.8 As the photographer Bernice Abbott wrote in 1951:

A photograph is not a painting, a poem, a symphony, a dance. It is not just a pretty picture, not an exercise in contortionist techniques and sheer print quality. It is or should be a significant document, a penetrating statement, which can be described in a very simple term: selectivity.9

The images created by cameras were thus a new kind of visual hybrid: products of a momentary liaison between chance and contrivance, and between the automaticity of the camera’s mechanisms and the purposeful action of its operator. “If everything that existed were continually being photographed”, John Berger once observed, “every photograph would become meaningless.”10 Photography could argue on this basis that it was the most worldly of the arts, the activity most in tune with the pulse of things. In contrast with traditional painting, so often patiently practiced behind the closed doors of the studio where the artist works from a scene carefully arranged beforehand, the photographer is the paragon of a modern sensibility, of historical consciousness and cosmopolitanism, throwing himself into the flow of real events, and explaining the world—though not judging it—only by attentively observing it, and putting it on display for all to see.

The fact that the camera’s simple technology turned out to be capable of such unexpected and contradictory revelations—of seeming to disclose the world objectively, while also emphasizing the inherent situatedness of all spatialized vision; of dryly documenting reality in the form of ‘accurate’ information, while also validating our sentimental response to these images, with their talismanic power to bring into presence a trace of what is absent; and of generally showing us the world anew, making the familiar appear strange, and the strange oddly familiar. With its special gift for reframing reality, the camera also called into question customary evaluations of high and low, of dignity and baseness, managing to beautify what is usually judged ugly,11 or, with an impertinent presentation, to denigrate what is considered respectable. The photograph had now firmly established itself as one of the defining accessories of modern life, ubiquitous in photo albums, on office desks, above the staircases of suburban homes, in the pages of books, magazines, and newspapers, and indispensable in corporate advertising, apparatuses of state surveillance, military intelligence, and policing. All this helped to make the photographic inundation so enigmatic and irresistible for would-be interpreters of the changing image-world.

The camera remade the vision of those who take photographs just as surely as those who look at them. The consumers of images, now surrounded by photographs, are not sated by the supply; we demand to be filled with images of every imaginable scene, which in turn feeds the voracious appetite for yet more images. For photographers, the apparatus of the camera extends the vision and encourages the hunt for new things to photograph; we imagine that the camera confers not just a right, but a duty to capture and reproduce the sights and experiences made available by modernity’s dynamic campaign to make the world accessible. The trespasses of the camera’s gaze are excused, its aggressions redeemed, by the supposed imperative that there be still more photographs, that the unceasing passing away of things be arrested by the never-ending task of recording, cataloging, and indexing the visual universe. The photographing eye—human vision as it is transformed through its extension by a camera—truly is “the ideal arm of consciousness in its acquisitive mood”.12

For all of us, the image-world composed of photographs introduced more than simply an unfamiliar “grammar” in the way things and images relate to each other; it introduced a new “ethics of seeing”.13 The camera neither reversed the power of images to deceive, nor did it overturn the capacity of the human mind to know, but its consequences—which didn’t just increase the quantity but changed the very nature of the images we see—forever restructured the syntax of the image-world and placed us into a new relationship with it. As the photographer Edward Weston perceived in 1932, writing in one of his journals, or “daybooks”: “Old ideals are crashing on all sides, and the precise uncompromising camera vision is, and will be made so, a world force in the revaluation of life.”14

Continue to Part II.

John Berger, “Appearances”, in Understanding a Photograph, pg. 67.

William Henry Fox Talbot, The Pencil of Nature, pg. 1.

I borrow the metaphor from John Berger, “Appearances”, in Understanding a Photograph, pg. 69.

Robert Lowell, “Epilogue”, 1977.

László Moholy-Nagy, Painting Photography Film, pg. 28. Italics mine.

“[A] precise form of representation”, Moholy-Nagy wrote, “so objective as to permit of no individual interpretation.” “Typophoto” (1925)

John Berger, “Understanding a Photograph” in Understanding a Photograph, pg. 19.

Ibid.

Berenice Abbott, “Photography at the Crossroads” (1951)

John Berger, “Understanding a Photograph”, in Understanding a Photograph, pg. 18.

See Irving Penn’s collection of photographs of discarded cigarette butts, in which the attention of the camera alone seems to confer upon its subject an incongruous dignity.

Susan Sontag, “In Plato’s Cave”, in On Photography, pg. 3-4.

Ibid., pg. 3 (italics mine).

Edward Weston, Daybooks Vol. II, pg. 229.