All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace

Reflections on the “humanity of the gaps” and techno-humanism

Welcome to Ever Not Quite—essays about technology and humanism. If this is the first post you’re receiving as a subscriber to the newsletter—welcome! I’m glad you’ve found your way here.

I began the line of thought that grew into this essay modestly, by wondering about our expressions of enthusiasm for technological innovation—for new things and gadgets generally. Why do such feats of engineering elicit, for instance, the reflexive use of the word “cool” so readily and so reliably? But that isn’t what this essay is about; from there, I began to speculate about the implications of taking seriously the idea that technological capabilities have no inherent limitations—that perhaps just about everything is, at least in theory, technologically possible. It surely matters whether we believe this to be true or not—and if we do, what does that suggest about what we think we’re doing with technology, and what its history and future represent?

I had intended for this post to be a short reflection on these themes and observations, but soon it became clear that I had wandered into some serious issues, and I decided to accept the opportunity to linger and explore them in greater depth. I began to consider the idea of what has been called the “humanity of the gaps”, that is, as machines become capable of more and more, we begin to define ourselves by contrast with them, locating our humanity in our ability to do what no machine can yet do. We frequently encounter attempts to quell fears about human obsolescence which urge that a more automated world, in which machines have taken over much or all of what is currently human labor, presents unprecedented opportunities for us to discover something new and profound about our own humanity. According to some versions of this view, whatever machines become capable of doing, this can only present us with opportunities to embrace our humanity all the more completely, and to develop more fully into our true nature: no machine can ever do everything we can do, so each advance only serves to elevate our unique abilities. I worry that these expressions of optimism suffer from two major shortcomings: first, the deeply unimaginative assumption that machines will never be capable of matching or surpassing human skills, and second, the implicitly utilitarian understanding of human purpose which reduces us to our functions and presses us into competition with machines in the first place.

I conclude with a few thoughts about techno-humanism, a perspective which manages to avoid some of these difficulties, but which tends, in the process, to deliver us over to the contingencies of technological change and implicitly encourages a posture of acquiescence to its pressures.

As always, what follows is a consideration of these issues as I have come to understand them—characterizations are incomplete, proposals are exploratory, and conclusions are tentative. And of course, I have provided an audio reading of the essay for those who would rather look away from the screen.

During one of the many charismatic expatiations that amassed his loyal following in 1990s psychedelic techno-culture, Terence McKenna once related an anecdote about one of his visits to the Amazon in the early 1970s. The group had arrived in the village by boat wielding assorted technological artifacts not familiar to the locals: outboard motors, photography equipment, butterfly nets, velcro. Unlike most of the villagers, whose amazement at such things might be said to resemble the awe which the denizens of modern industrial societies frequently exhibit towards novel devices (the Apple Vision Pro is only the most recent example), it was the village shaman alone who remained impassive upon the presentation of this display which so mesmerized the others. McKenna’s lesson here was that, unlike the other villagers, the shaman has an uncommon intimacy with the workings of all things magical: having witnessed their operation, and engaged their mysterious machinations, the shaman stood unmoved by the peculiar paraphernalia brought forward by this curious group of foreigners.

Now, I make no claim one way or the other about the veracity of McKenna’s story—nor about the legitimacy of his interpretation of these diverging reactions. My intention here is simply to comment upon the good sense, be it genuine or a work of fiction, of the shaman in this story, in this aloofness and almost passive resistance to the popular inclination to meet new technologies with a naïve and uncritical fascination. Indeed, I want to suggest that we ourselves strive to accept all the more thoroughly what is perhaps already obvious: that the engineers who design and fabricate new technologies are exceptionally capable—and are likely to become ever more capable—of bodying forth what only a short time ago was understood to be beyond our technical reach, and perhaps even to surpass our concept of the possible.

The twentieth century sci-fi author and futurist Arthur C. Clarke once introduced three “laws”, the last of which comes to mind in this connection: Clarke famously posited that “[a]ny sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.”1 He meant, if I may be permitted to interpret his meaning, that the success of the most advanced technologies seems to challenge the very laws of nature as we understand them, and to make possible what, on strictly naturalistic grounds, should not be possible at all. But the irony embedded within Clarke’s dictum is that technology is in fact not magic in any sense of the word—that it works quite comfortably within the constraints imposed upon reality by the orderly functioning of nature: that is to say, superseding the laws of nature is altogether unnecessary in the fabrication of crafts that possess powers that may appear most unnatural.

Clarke thought the process of encoding ever more of this apparent magic into matter was entirely inevitable, which is not a position I happen to share.2 But it seems to me that he has captured something significant here: the point is that there are no meaningful limitations to what technology can accomplish, even on its own strictly naturalistic terms, and that any intuition to the contrary will likely be revealed before long to be mistaken. Although technology is forever fixed within the matrix of nature’s laws, the constraints within which it operates nonetheless allow for a latitude that is practically inexhaustible. For many, artificial intelligence has been the technology which has done more than any other to make this situation clear: despite continued warnings from a number of prominent skeptics3 who argue that the era of low-hanging fruit and fast-paced advance is nearing its end, AI has accomplished some astounding things which, just a few years ago, most did not consider to be imminent—or even compatible with the very nature of artificial consciousness, creativity, or agency.

Charles Holland Duell, who was Commissioner of the United States Patent Office from 1898 to 1901 is sometimes said to have given utterance to the notorious folly: “Everything that can be invented has been invented”. This is not actually true—Duell said no such thing, and the source of this quip remains mysterious, although it probably originated with a joke in an 1899 edition of Punch magazine. But the reason we still remember this remark, I think, is that we find humor in the very idea which it expresses—that invention could ever exhaust itself—and that it seems to state with such glib confidence, and in the voice of a person in the best imaginable position to know better, the exact opposite of the truth. Indeed, most would probably agree that there will never come a time at which everything that could be invented had already been invented—let alone that we might have reached this point sometime around the end of the nineteenth century. And if that is true—if the scope of what is technologically accessible to human ingenuity has no inherent or meaningful limitations, then I suggest that we consider one major implication of this peculiar circumstance.

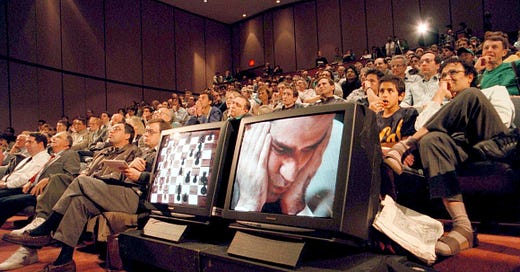

In a recent podcast, Krista Tippett remarked how, when we think about a world of widespread AI automation, we often find consolation in what she calls the “humanity of the gaps”: that is, we define ourselves in contrast to the capabilities of any machine, locating our humanity in our ability to occupy whatever zones of technological incompetence continue to exist. We feel—or at least some do—that we have collectively lost something whenever a computer defeats the World Chess Champion in a tournament, say, or when the world’s top human player is defeated in a game of Go by a computer program, or when the best human Jeopardy! players are defeated by an AI in a real-time, natural language game. But all of these things have happened within the last few decades. Each time, however, we have taken comfort in the idea that, while we may have been bested by a computer in some particular area, there is still plenty that we can do that the computer cannot, that the specific skill in question never really defined us anyway, and so we manage to retain our sense of our own prestige.4

In his 2016 book, The Inevitable: Understanding the 12 Technological Forces That Will Shape Our Future, the futurist writer Kevin Kelly quite accurately observes that as this process has unfolded, “we’ve been redefining what it means to be human.” This is a way of saying that our sense of ourselves—of what we really are, of what gives us value—has become entangled with the history of technology. This observation is perhaps not very surprising or controversial; human-made artifacts have always shaped our experience of the world and our understanding of ourselves. But Kelly continues:

Over the past 60 years, as mechanical processes have replicated behaviors and talents we thought were unique to humans, we’ve had to change our minds about what sets us apart. As we invent more species of AI, we will be forced to surrender more of what is supposedly unique about humans. Each step of surrender—we are not the only mind that can play chess, fly a plane, make music or invent a mathematical law—will be painful and sad. We’ll spend the next three decades—indeed, perhaps the next century—in a permanent identity crisis, continually asking ourselves what humans are good for. If we aren’t unique toolmakers, or artists, or moral ethicists, then what, if anything, makes us special?5

And I would add that, because it specializes in tasks that don’t manipulate the physical world, but only orchestrate an abstract world of information and tactics, computer technology is unique in its ability to mimic and substitute for the rational functions which we have long imagined to be the exclusive human endowment.

Indeed, speculations concerning the human essence—whatever it is that distinguishes us from everything else—have an ancient pedigree. In modern scientific taxonomy, our self-definition Homo sapiens—or, “wise man”—is only a fresh permutation of Aristotle’s much older “animal rationale”, which has been variously supported and challenged by philosophers and anthropologists for centuries.6 Like many classical definitions of the human being that no longer feel as though they capture something essential about us, any attempt to define ourselves according to the negative space that is delineated by the competencies of technology is, I suspect, untenable; we are already aware, if discomfited, by the (increasingly plausible) idea that there may ultimately be no task that we alone can, in principle, perform. In fact, it is no longer outside the bounds of polite discourse to suggest that perhaps we can—or even should—be replaced by machines more capable than ourselves, regardless of the nature of the activity in question.

Metaphorically speaking, it is as though we find ourselves on a shrinking ice floe representing the last of our unique capabilities—a condition that augurs our total reabsorption back into nature’s vast, inclusive inventory of things.7 That is, when we cease to be secured safely on the elevated plane that upholds our superiority over beings of every other type, we discover ourselves to have become things just like anything else; and if we become a part of nature, and if nature has itself already been conceived as a kind of machine, then—following an ancient syllogism—we too will have become machines ourselves. Thus, the terror of antiquity at the prospect of being debased when we allow ourselves to become enthralled by our passions, and thus to become no more than a subhuman beast, yields to the distinctly modern dread of discovering that we have become not a beast, but just another machine. (Indeed, the modern world has largely rehabilitated our estimation of the passions precisely on the grounds that they link us to a more authentic and organic animality, and separate us from the cold calculations of machine cognition.8) Far from worrying that the forfeiture of our own rational faculties would entail the loss of our exalted place in the chain of being, the modern anxiety springs from the fact that machines, too, have acquired rational faculties of their own, preparing our displacement rather than concluding our degradation.

The concept of the “humanity of the gaps” plays on the older theological notion of the “God of the gaps”—the idea that, as modern science has offered an increasingly thorough and detailed model of formerly unaccountable natural phenomena, there has been less and less need to invoke the hand of God as a supernatural intervention necessary to guide the unceasing cycles and swerves that constitute the functioning of nature. It has frequently been pointed out that the consequence of the disappearance of any trace of the supernatural in our understanding of nature has been that, with the advance of a wholly naturalistic and mechanical account, some sacred element is thrust into perpetual retreat as the scientific, secular one is recognized and encouraged to grow ever more self-assured; the result is the now-familiar flattened and desacralized world about which much has been written in the last century, and readers will respond to this interpretation in different ways. But I am tempted to think that this is all largely beside the issue at hand: sacredness does not, and never did, rest upon human ignorance of causes. As the German theologian and anti-Nazi dissident Dietrich Bonhoeffer once wrote from prison to a friend: “We are to find God in what we know, not in what we don’t know.” Something analogous, I think, can be said of our situation relative to the capabilities of machines.

In an op-ed in the New York Times early last year, David Brooks encouraged his readers—and especially the young among them—to pursue an education that aims to refine what he calls “distinctly human skills”. “[T]he core reality of the coming A.I. age”, he writes, is that, while much of the mental work that has historically consumed a large portion of highly-trained human labor will begin to be done by machines, their fruits will continue to be bland, derivative, and steeped in the clichés of official consensus; AI will forever lack the singular perspective and voice which remains the sole patrimony of human idiosyncrasy. Persuaded of the enduring incompetence of artificial intelligence, Brooks advises his readers to develop skills which, he says, “unleash your creativity, that give you a chance to exercise and hone your imaginative powers.” He exhorts young writers “to develop a voice as distinct as those of George Orwell, Joan Didion, Tom Wolfe and James Baldwin”. Only this human capacity, Brooks urges, remains safe from the emerging future that will be dominated by automation.

“A.I. will force us humans to double down on those talents and skills that only humans possess”, Brooks writes. “The most important thing about A.I.”, he continues, “may be that it shows us what it can’t do, and so reveals who we are and what we have to offer.” In other words, we have here an argument of a familiar variety: our humanity is what fills the gaps left behind by the machine; AI will never synthesize the kind of unique perspective on the world that is the hallmark of the idiosyncratic, creative, and self-expressing human being. And Brooks is not alone in advancing a version of this palliative: over the last year, we have heard plenty of similar advice put forth to reassure the anxious that the coming world will continue to preserve fulfilling roles for which human beings are needed. Nor is this attitude entirely without merit: more than a year later, LLMs in particular really do tend to issue a banal epistemic average in their account of the world—and to the degree to which they fail to do even this, tech companies are hard at work to make their models better conform to consensus-reality. But it is easy to take refuge in this sort of argument, comforted by the limitations of the technology in its current form, due only to the fact that its shortcomings happen to preserve a gap large enough to be inhabited by the eccentric dimensions of a distinctly human element.

But if this is the most robust consolation on offer, I worry that we’re in trouble. It is something like reassuring a polar bear that the remaining ice, notwithstanding all its conspicuous melting, is still capable of supporting most of its weight—and concluding that we have somehow acted to mitigate the processes that have set this situation into motion in the first place. As implausible as it may sound at the moment to imagine that a machine could develop the unique writerly style and perspective on the world that remains the exclusive domain of extraordinary (human) writers, it is not impossible that we will eventually find ourselves once again clambering for new territory upon which to raise the human flag. I’m afraid that Brooks’ argument and others like it, which are intended as a solace, suffer from a profound failure of imagination: they assume that technology is not capable of pushing beyond its present boundaries, and that it has already achieved all that it ever will—in a word, it assumes that everything that can be invented has been invented. Strangely, the wonder which we often experience upon encountering a new technology capable of doing much more than we thought possible here mutates into a kind of denialism; it is as though we say: this machine is so amazing that it must surely represent the end of its progress—thus far you shall come, but no farther!

To my mind, these forecasts for human indispensability in an automated world make two important errors: first, they lean too heavily on the (increasingly conjectural) assumption that no machine will ever be capable of doing everything that we can do, that there is some quintessentially human activity that no technology could ever replicate. And this denialism provides a rationale for disregarding the questions that would be raised by a situation in which human skill, initiative, and responsibility have ceded their animating role in economic and cultural production to the functions of machines—what we might call a condition of human obsolescence or, perhaps more charitably, of post-instrumentality.9 Rather, they suggest that the mandate for human beings in the new machine age will be (or perhaps already is) simply to identify and refine those tasks and activities that still make us uniquely necessary, continually reinterpreting ourselves according to their limitations. The second error, closely related to the first, is that, the more we believe that the emancipation of our deepest humanity is accomplished specifically by the failures of machine competency, the more we will tend to conceive of the highest reaches of our activity in terms of expediency and utility.

To be sure, many critics continue to argue—and quite effectively—that technologies are often not as successful as they are claimed to be by those who develop them. The reason machines will never replace human intellect or creativity, they maintain, is that they don’t actually possess these qualities in the first place; their success is limited to simple mimicry, and to the gullible persuasion that these capacities are authentic expressions of an underlying artificial consciousness and imagination. It is important to be alert to the ways that, indeed, artificial intelligence and machine learning, are in truth misnomers: metaphors, at best, for their genuine appearance in living organisms. But inasmuch as the issue concerns the ability of machines to act in the world, it is irrelevant that these features are only appearances, or that AI is capable of producing only what it has appropriated from what were originally the fruits of human craft; it is the effectiveness of machines alone, which is real enough, that exposes human skills to this sort of techno-memetic replacement.

Similarly, the pragmatic observation that, regardless of any authentic substance that may be thought to lie behind their capacities, machines are nowhere near actually replacing human beings, only sidesteps the question, drawing its horizon closer to the realities of the present without challenging in principle the technical possibility—or even the wisdom—of engineering them into existence in the first place. However irreconcilable it may be with what remains of our self-image as superior beings, these machines do indeed work, at least according to the terms which they set for themselves, and it stands to reason that they will continue to make an ever-stronger argument in favor of their capabilities, and against the distinctiveness of our own; those who endeavor to define the signature human trait or talent—the one never to be matched by any machine—provide little contingency for the interminable, yet foreseeable, erosion of our singular claim upon it. Practically speaking, the skepticism about technology’s prospects for greater and greater functionality which lies at the heart of this view forfeits any opportunity to consider seriously what a condition of human post-instrumentality might actually mean, ceding that ground instead to the optimistic drift of futurists and technologists, whose positive assessment is virtually guaranteed.

But even more fundamentally, when we find ourselves validating human belonging in the world on the basis of our ability to be uniquely useful in some way—however sophisticated our peculiar task or activity may be—we assume that our place on earth derives exclusively from what we can do, in how we may be put to work. In other words, we bring to bear a set of inherently instrumental assumptions according to which we interpret ourselves through the lens of our usefulness. However implausible their implicit presumption of technological stasis, arguments like the one advanced by Brooks do indeed offer a vision of human purpose in an age of automation, but it is one that is forced by the pressures of creeping automation to exalt our capacity for useful production. It is no coincidence that Brooks emphasizes a model of education that views it essentially as a kind of future-proof career training: young writers must learn to do what no machine could ever do—to write with voice and singular vision—and it is the task of educators to foster these important skills in their students.10

Against all of this, it seems to me that whatever it is that each of us might be able to contribute to the economy—whatever distinctive tasks we can perform, or economically-relevant skills we can master—all this is entirely beside the deeper issue that widespread automation raises: I want to suggest that the very idea that the human essence is located in what we alone can do reveals an already diminished understanding of the highest offices of our humanity. That is to say, we should be less concerned that machines will become capable of all that we are capable of, and more concerned that our preoccupation with expediency and utility demonstrates the degree to which we have allowed an implicitly technologized conception of ourselves to press us into competition with machines for a place in the world. As the theologian Josef Pieper puts it in his classic 20th-century essay, “Leisure: The Basis of Culture”, under the regime of what he calls “total work”, “[m]an, from this point of view, is essentially a functionary, an official, even in the highest reaches of his activity.”11

This is, of course, to invite the question: if we are not, ultimately, born simply in order to be useful in some larger economic scheme, what is the best way to think about life’s purposes? Readers will have differing ideas about how best to respond to this question, and I offer no definitive answer to it here. Pieper writes in another essay that only “[i]n the act of philosophizing, man’s relationship to being as a whole is realized—he is face to face with the whole of reality.”12 Just as Bonhoeffer wrote of God—that he is to be found in what we know, not in what we don’t know—I suspect that we will not discover our highest potentialities in that ever-shrinking portion of our skills which we can’t imagine any machine could ever be designed to replicate: arguments that wager the essence either of the holy or the authentically human against what science can know and what technology can do unwittingly ordain techno-scientific failure as the mark of sanctification.

I had intended to conclude this essay, and to set this topic aside for now, with the foregoing observations. But there is one more point I want to make, now that I find that I have wandered up to the threshold of another important approach to these issues. There is a contrasting view which recommends itself as an alternative to the implicit technological denialism and preoccupation with utility that underlie the perspective we’ve just been considering. In the paragraph I have already quoted above, Kevin Kelly formulates his own solution to the “humanity of the gaps” problem—one which neither denies the power of technology to mimic all human capabilities, nor relies excessively on utilitarian justifications for human residency in the world. But in the process, Kelly reveals what is, I think, another set of questionable assumptions regarding the human relationship with technology. Here’s Kelly again:

In the grandest irony of all, the greatest benefit of an everyday, utilitarian AI will not be increased productivity or an economics of abundance or a new way of doing science—although all those will happen. The greatest benefit of the arrival of artificial intelligence is that AIs will help define humanity. We need AIs to tell us who we are.13

Kelly doesn’t deny, as some do, that technology will eventually take over every task which is today performed by human beings (not to mention plenty which are not currently performed at all), nor does he regard human life, ultimately, under the sole aspect of instrumentality.14 Above all else, what is most striking in this passage is its explicit declaration of what we might call techno-humanism in its purest form: by liberating us from having to perform all the servile labor which is truly beneath our dignity, technology both enables and encourages us to take up more meaningful—that is, more essentially human—activities which cultivate those capacities that most contribute to our wholeness and fulfillment. Thus, technological advance as such draws us ever more consummately into the perfection of our own nature.

Although techno-humanism shares its emphasis on technological progress with trans-humanism, rather than overcoming human nature, it maintains that our essential wisdom—identified, of course, in our modern-day biological self-classification, Homo sapiens—is ultimately realized and enlarged by means of technology. As Reid Hoffman recently remarked even more radically in his own paean to techno-humanism, “[i]f we merely lived up to our scientific classification—Homo sapiens—and just sat around thinking all day, we’d be much different creatures than we actually are.” Rather, Hoffman ventures, extending a proud tradition of adapting the binomial formula, we best understand ourselves when we carry the epithet: Homo techne. “Technology”, Hoffman concludes: “is the thing that makes us us. Through the tools we create, we become neither less human nor superhuman, nor post-human. We become more human.” Now, whatever we make of this idea, and whatever role we wish to assign to technology in establishing human nature, what is clear is that it implies that technological progress is human progress—indeed, it suggests that the principal reason there can be such a thing as progress with regard to human things is that we acquire it second-hand, as it were, from the progress of technology.15

To the extent that we endorse these twin techno-humanist assumptions—that humanity is perfected by our capacity for the invention and use of technology, and that technological change and human history together trace a progressive contour—we will tend also to place our trust, and even our hope, in what we will come to call, with unstated approbation, technological innovation, and we will view its history not as a mere sequence of unconnected occurrences, but now as the unfolding, in Kelly’s vocabulary, of the inevitable. Stated somewhat differently, to the extent that we believe, implicitly or otherwise, that the increased sophistication of machines can only help to advance our own ascent into the highest precincts of our nature, we will also incline to the view that the logic that unfolds throughout the history of technology is an inherently progressive and altogether inevitable one. Now, perhaps this is true, and perhaps some readers will wish to grant some or all of the techno-humanist standpoint. But my purpose in pointing out these consequences is that our trust in what are at least questionable presumptions can make it appear as though, whatever work machines have been trained to do, and whatever responsibilities they have been invested with, greater fulfillment awaits us on the other side of the the social, economic, and psychological adjustments that will be demanded by technology’s dispensations. And this is why, it seems to me, techno-humanism (or something like it) quietly abets our willingness—often exhibited in the form of awe, wonder, and enthusiasm—to be conditioned by the contingencies of novel technologies.

Here’s my suggestion. Let’s cultivate as a virtue the impassivity of Terence McKenna’s shaman, who maintains a certain critical distance from the artifacts that are brought forward out of the belly of corporate R&D departments, and recognize them for what they more realistically are: particular techno-cultural expressions of the ideals and narratives that populate the minds of technologists who would design the world according to their own image of perfection, and not the advancement of any ultimate human destiny. If we acknowledge at the outset that all things may perhaps be technically possible, there will be no reason to yield to astonishment, to be drawn uncritically to the wonders that engineering has made real, or ultimately to allow awe to devolve into acquiescence. Above all, let’s not assume that technology will complete us—as individuals or as a culture—as a reliable matter of course. Jean-Paul Sartre is often (apocryphally) reputed to have said that “[e]verything has been figured out except how to live.”16 Surely, when it comes to our relationship with technology, these words become truer every day.

Indeed, all three of Clarke’s laws, which first appear in his 1962 essay “Hazards of Prophecy: The Failure of Imagination”, are relevant to my purposes here. The three laws read:

When a distinguished but elderly scientist states that something is possible, he is almost certainly right. When he states that something is impossible, he is very probably wrong.

The only way of discovering the limits of the possible is to venture a little way past them into the impossible.

Any sufficiently advanced technology is indistinguishable from magic.

Here is an interesting clip of some of Clarke’s prognostications from 1964, which are striking to rewatch today.

As the computer scientist Douglas Hofstadter told the New York Times of Garry Kasparov’s watershed defeat by DeepBlue in 1996: “[Computers] are just overtaking humans in certain intellectual activities that we thought required intelligence. My God, I used to think chess required thought. Now, I realize it doesn’t. It doesn’t mean Kasparov isn’t a deep thinker, just that you can bypass deep thinking in playing chess, the way you can fly without flapping your wings.”

Kevin Kelly, The Inevitable: Understanding the 12 Technological Forces That Will Shape Our Future, pg. 48.

See Aristotle, On the Soul, III.11 and Nicomachean Ethics, I.13.

Here I am reminded of Richard Brautigan’s 1967 poem, “All Watched Over by Machines of Loving Grace”. The last stanza illustrates the scene particularly vividly:

I like to think (it has to be!) of a cybernetic ecology where we are free of our labors and joined back to nature, returned to our mammal brothers and sisters, and all watched over by machines of loving grace.

The recent popularity of Stoicism is perhaps a noteworthy counterexample to this point.

This last term is the preferred locution of Nick Bostrom’s new book, Deep Utopia: Life and Meaning in a Solved World.

I don’t mean to single out Brooks here, nor to insinuate that this represents Brooks’ final word on the subject of education. For a more complete picture, I refer the reader to his piece in The Atlantic from last summer, “How America Got Mean”, which pays considerable attention to the role of educational institutions in what he calls “character formation”. Here, I have simply chosen Brooks to serve as a spokesperson for a common perspective.

Late last year, I wrote about what I called the “revenge of the liberal arts”, by which I meant the way that liberal arts education, long considered moribund, could discover a newfound relevance under the conditions of an automated economy which no longer demands that human beings acquire the “useful” skills necessary to keep it running.

Josef Pieper, “Leisure: The Basis of Culture” in Leisure: The Basis of Culture, pg. 38 (italics mine).

Josef Pieper, “The Philosophical Act” in Leisure: The Basis of Culture, pg. 127.

Kevin Kelly, The Inevitable: Understanding the 12 Technological Forces That Will Shape Our Future, pg. 48-9 (italics mine).

On the first point about the in-principle replaceability of all human activity by machines, Kelly summarizes what he calls the “Seven Stages of Robotic Replacement”:

1. A robot/computer cannot possibly do the tasks I do. 2. [Later.] OK, it can do a lot of those tasks, but it can’t do everything I do. 3. [Later.] OK. it can do everything I do, except it needs me when it breaks down, which is often. 4. [Later.] OK, it operates flawlessly on routine stuff, but I need to train it for new tasks. 5. [Later.] OK, OK, it can have my old boring job, because it’s obvious that was not a job that humans were meant to do. 6. [Later.] Wow, now that robots are doing my old job, my new job is much more interesting and pays more! 7. [Later.] I am so glad a robot/computer cannot possibly do what I do now. [Repeat.]

Indeed we can push this observation further still, and note that a perspective like techno-humanism is itself only possible in a context such as that of the rapid technological change of the last several centuries. It is, in a strong sense, a historically contingent view in that it would have been considered an unthinkable position prior to the modern era.

The phrase has a genealogy that traces, by way of the child psychologist Robert Coles, back to a statement by Søren Kierkegaard. Coles wrote in 1978 that “Kierkegaard’s nineteenth century grievance—that the increased knowledge of his time enabled people to understand, or think they would soon understand, just about everything except how to live a life—might well be our complaint too.” Kierkegaard once wrote that “[o]ne thing has always escaped Hegel, and that is how to live.” But the version so often misattributed to Sartre is most effective for my purposes here.

https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s10676-024-09775-5

Excellent essay. Ivan Illich has also touched on the same issues.

Very, very good. Strange analogy/harmony: Raina Raskin has a Mother's Day essay "How Motherhood Liberated Me" is about a life spent in our competitive world, trying to be extraordinary, and finding meaning in breast feeding, which isn't even specific to humans: "And now, here I was, doing something that literally defines the female mammal. "

"https://www.thefp.com/p/motherhood-liberated-me-mothers-day?r=13evep&utm_campaign=post&utm_medium=web

I think there are philosophical reasons to see "the human" as that which is singular to humans, thus in the gaps left by technologies. "Ding an sich," "PURE reason," a bunch of Aristotle, usw. And it comes very naturally, as Raskin discusses, in commercial societies. Why are you "the best" or at least "the best value" or "best available" at X. But, comparisons are invidious . . . again, very nicely done, helped my own thinking, thank you.