Happy New Year! And welcome to Ever Not Quite, a newsletter about technology and humanism. This essay responds to what I call a “strange fissure” that seems to run through modern technologists, who possess a technical competence that gives them authority over those who don’t share their expertise, but who nonetheless remain human beings whose perspective is still rooted in the same human experiences as the rest of us. At bottom, this fissure demarcates two ways of conceiving the world: one scientifically objective, having freed itself of any particular interest in human concerns as such, and another social and political outlook that is ineluctably rooted in a human standpoint. How best to think about this internal division has been the subject of much debate for centuries now.

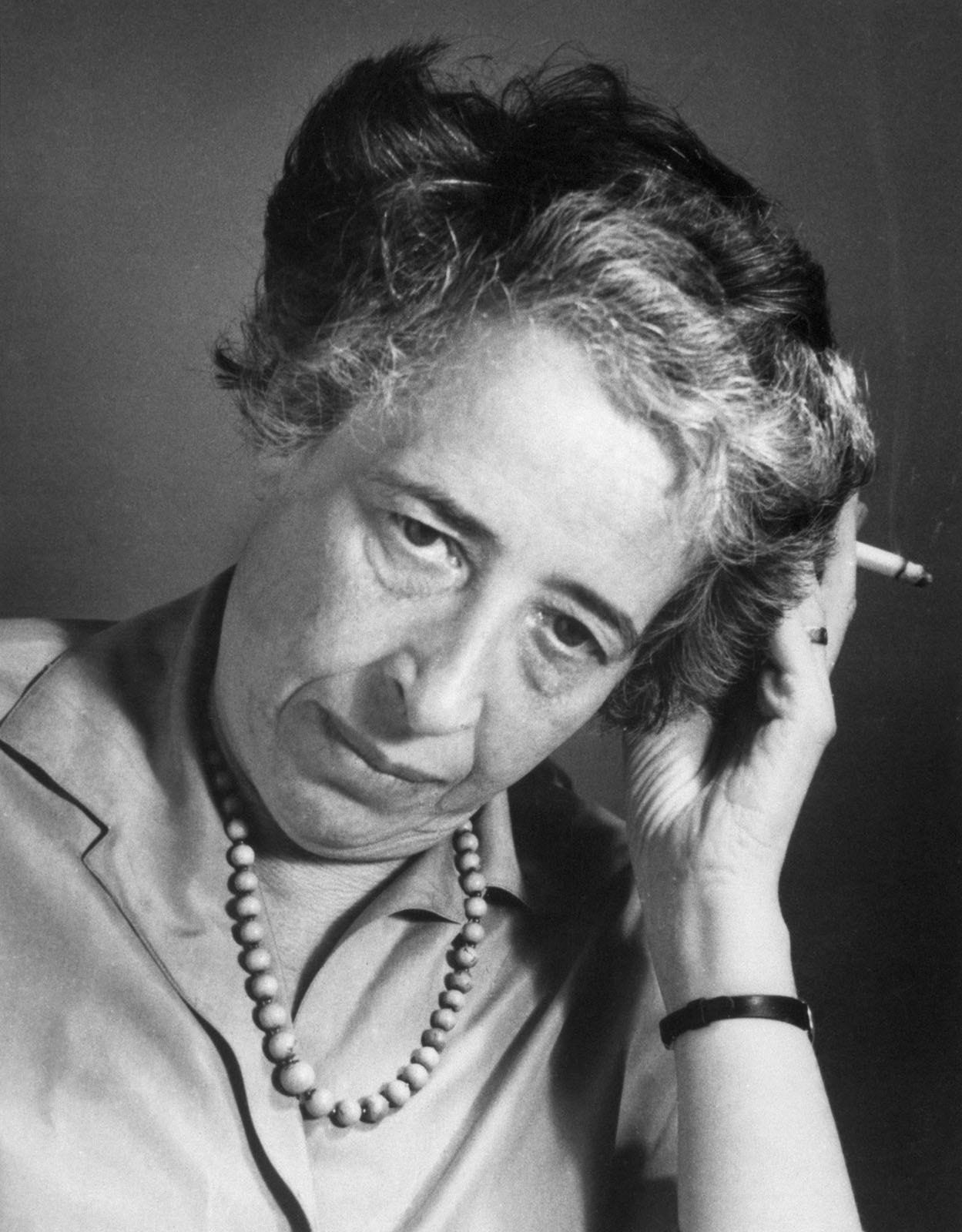

Here, I argue that perennial debates about the relationship between politics and expertise continue to reverberate through our contemporary discourse about the human implications of artificial intelligence and the algorithmic management of our world. The emergence of AI in particular raises questions about the place of the human being in the universe that echo those posed by the prospect of space travel in the mid-20th century; in both cases, technological devices and practices take up and reflect a prior theoretical displacement of the human being within the immensity of the universe. I look to Hannah Arendt’s short 1963 essay “The Conquest of Space and the Stature of Man”, which proves to be a surprisingly relevant and prescient guide to these topics.

I hope you find it interesting, and as always, thank you for reading!

It was last spring, as the potential significance of AI for humanity was beginning to infiltrate the public imagination, that many people first heard about artificial general intelligence and its concomitant risks. In March, in a harrowing op-ed in Time Magazine, the artificial intelligence researcher Eliezer Yudkowsky wrote:

Some of my friends have recently reported to me that when people outside the AI industry hear about extinction risk from Artificial General Intelligence for the first time, their reaction is “maybe we should not build AGI, then.”

The intuitive wisdom of this reaction coupled with its stark contrast with the determined actions of researchers and experts who continue to busy themselves with pressing the technology forward, was a telling indication of a deeper divergence: what is obvious to the layperson, it seems, is not at all obvious to the expert. Or, to put it perhaps more precisely, inasmuch as the experts had no trouble recognizing the dangers involved in what they were doing, there was apparently little they could actually do to reverse course and stop it—despite the fact that it was they themselves who were doing it. And in the months since, it has become commonplace to hear high-level researchers publicly conceding that their work, if pursued incautiously—or pursued at all, depending on whom you ask—is in danger of yielding utterly dystopian outcomes.1 In light of all this, the natural conclusion is that, apart from the pat observation that we deal here with yet another instance of the classic multipolar trap, there exists a strange fissure that runs through these technologists themselves which separates what they are capable of accomplishing by virtue of their skills as engineers from the human values they still claim to hold.

Back in November, the computer scientist Fei-Fei Li described the highly rarefied environment in which the AI scientists employed by major tech companies work, and the large salaries and many perks of employment with which they are compensated. The picture that emerges depicts a privileged group of people who are completely out of touch with—and, notwithstanding the much-publicized tech industry layoffs of the past year, largely untouchable by—the real world that is experienced by most everybody else, despite the fact that this world stands to be irrevocably altered by the fruits of their research. Li argues for efforts that could begin to close the gap between tech-insiders and the wider social and political world of which we are all a part. “The time has come”, Li writes, “to reevaluate the way AI is taught at every level. The practitioners of the coming years will need much more than technological expertise; they’ll have to understand philosophy, and ethics, and even law.” They’ll need, in other words, something more than the technical expertise which continues to be the only real qualification to work in the field: the products of their research will be so powerful that they’ll also need some acquaintance with the humane disciplines with which their inventions interfere. In short, Li concludes, “AI must become as committed to humanity as it’s always been to science.”

I should say clearly that I sympathize with the intentions behind this argument. Technologists urgently need, at a minimum, to be better apprised of what is at stake for the larger world that is inevitably shaped by their designs and decisions. But I must also question the coherence of this kind of argument at the most fundamental level: is it possible in principle for science and technology to absorb humanistic considerations without falling into a kind of contradiction? As encouraging as it is to hear these chastening sentiments coming directly from someone at the center of AI research and development, I remain skeptical of the proposed alliance between modern techno-science and an ill-defined humanism that seems to be introduced as a last-minute corrective: there are divisions here, I think, that run too deep to be solved simply by more broadly educating the next generation of scientists and Silicon Valley insiders.

We have all been conditioned in certain habits of mind that encourage us to look to those with technical expertise to make crucial decisions about how science and technology will be conducted and developed. This derives, I think, from the well-founded and historically much older observation that those who possess genuine knowledge in a given area ought to have command over it. There are intuitive reasons for this which barely require explanation. In Western political thought, the idea of technocracy—the view that control over political affairs should be in the hands of those who possess technical knowledge about how things work—was among the earliest to emerge as an answer to what is perhaps the primary political question: who should rule and on what basis? But this creates a secondary problem concerning how this knowledge is to be recognized in the first place. Many of the people contending for rulership, it seems, know nothing at all about statecraft: what they possess instead is a certain skill in persuading others that they possess the requisite knowledge to rule, without so much as an ounce of the real thing. The political arena has long echoed with the bluster of bullshit artists vying for our attention and credulity.

Plato famously made it a major preoccupation of his philosophical and political investigations to distinguish between these know-nothing rhetoricians and those with real knowledge, and our well-founded intuition that important decisions about complicated matters should be made by genuine experts finds its earliest theoretical articulations in these speculations.2 In the Republic, the authority of the would-be political rulers derives from their unique perception of the world as it really is, quite apart from the way things appear to the many, who lack the education and wisdom necessary to rule. The important point here is that legitimate political rulership is connected to the possession of a certain kind of knowledge, and this knowledge—which is rare and difficult to obtain—excludes most citizens from consideration for holding political power. Today, the reverence we have for scientific expertise and our trust in its ability to direct public policy treads on a similar line of reasoning that ancient Greek political philosophers discovered in order to establish the foundations of political authority: The right of scientific experts to be believed and followed flows from their apprehension of a more real, yet hidden, reality to which the rest of us lack access, and which, therefore, makes them more suited than anyone else to render decisions that will be consequential for everyone. Only by becoming one of them through the right kind of education—and thereby learning to see how things really work—does one acquire the right to speak with the aura of scientific authority.

But the nature and stakes of scientific and technological expertise under modern techno-scientific conditions are different in important ways from these considerations as they first appeared in ancient Greek political thought. Although the Greeks by and large did not think the human was the noblest of beings—Aristotle explicitly states at one point that “man is not the highest thing in the world”—it was understood that the political realm was the venue of all quintessentially human endeavors, and was therefore to be governed by principles different from those that operate in the cosmos at large.3 Given this, it would have been unthinkable to imagine that those physicists who inquire about the makeup of the cosmos—who pursued what was then called “natural philosophy” and not yet “science”—to wrest control over politics from its rightful rulers, whether these were thought to be a democratic citizenry, an aristocratic class, or a monarch. Today, to the degree that our modern world resembles a scientific technocracy, its most relevant feature as concerns its influence on human affairs isn’t simply that scientific and technical experts know a great deal more about nature and how to control it than non-experts do; rather, it’s that scientific research takes for granted a set of presuppositions entirely different from those assumed in political life—presuppositions that from the outset are agnostic about the place or value of human endeavors within the unimaginably vast scope of the universe as a whole.

Of course, this is not some accidental and lamentable defect: from its own vantage, it is the great triumph of modern science that it has found a viewpoint on the universe that is, so to speak, “objective”, and has adopted the perspective that the philosopher Thomas Nagel has called “the view from nowhere”. As the philosophers Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison have described scientific objectivity as it developed in the nineteenth century, “[t]o be objective is to aspire to knowledge that bears no trace of the knower—knowledge unmarked by prejudice or skill, fantasy or judgment, wishing or striving”.4 There is a kind of freedom and breadth in this expansive standpoint, which from the outset endeavors simply to uncover truths—the more universal the better—that are unbeholden to our parochial and all-too-human presuppositions about hierarchy and precedent; liberated from these concerns, science aims merely to uncover general laws that are as valid on earth as they are in a galaxy on the other side of the universe.

But even this doesn’t fully capture the divergence between modern scientific knowledge and the ways of knowing that are available to the majority of non-experts: more than simply desituating the human being from the cosmic order within which it once found its natural place, modern science—and modern physics above all—has ceased even to conceive of nature in terms that are communicable by means of any natural human language. Not only has a mathematical language taken the place of a vernacular that communicates easily between non-specialists, it was ultimately conceded in the 20th-century that any thorough account of physical reality is actually inconceivable to the human mind. As the quantum physicist Erwin Schrödinger, referring to simplified models intended to make difficult concepts graspable for the layperson, wrote in his 1951 book Science and Humanism: Physics in Our Time:

A completely satisfactory model of this type is not only practically inaccessible, but not even thinkable. Or, to be more precise, we can, of course, think it, but however we think it, it is wrong; not perhaps quite as meaningless as a “triangular circle,” but much more so than a “winged lion.”5

Or, as the theoretical physicist Richard Feynman put it even more bluntly in a lecture decades later, “I hope you can accept Nature as She is—absurd.”6 In other words, the pursuit of the highest methodological ideals of modern science—objectivity and universality—has yielded scientific truths that are utterly alien and indeed inimical to human comprehension.

In 1963, the editors of Great Ideas Today posed a question to several high-profile scholars of diverse perspectives and interests for its “Symposium on Space”: “Has man’s conquest of space increased or diminished his stature?” The question was asked at a markedly different technological moment than our own, one whose foremost achievement was thought to be our novel escape—if only very temporarily—from the gravitational pull of the Earth. In April, 1961, the Soviet pilot Yuri Gagarin had been the first person to quit the earth’s gravity, and in the United States the first of the Apollo moon missions that would cap off the decade had been proclaimed by President Kennedy in a famous speech in September, 1962. The significance of this accomplishment has waned in the course of time, and today the stature of the human being within the scope of the universe no longer feels so directly tied to our ability to reach our nearest celestial neighbor as it once did.

Notwithstanding these differences between our respective technological moments, the question posed by Great Ideas Today rings loudly with the din of familiarity: like those who pondered such questions in the 1960s, we too are prompted to wonder about the effect of emerging technologies and practices on our own stature against the background of the universe. Today’s salient technological achievement—and the one which has us questioning anew our stature not in the universe but right here on earth—is the very real possibility that we will soon (if we haven’t already) find our cognitive abilities outmatched by the artificial computations of computer chips. Metaphorically speaking, the appearance of AI is less comparable to the unsettling caused by our ceasing as a species to be situated firmly on the Earth, and more to the visitation of our own planet by an intellectually superior species from someplace unimaginable: rather than displacing the center of the human world, the appearance of an exotic and superior intelligence challenges our sense of ascendency within the very heart of the earthly household.

The question has endured in an important reply by the political theorist Hannah Arendt, which later took its place as the final inclusion in her essay collection Between Past and Future in 1968. Arendt observed that, although the concern for the human stature is elicited by specific scientific and technological endeavors, it is not itself a scientific matter, properly understood. The question, Arendt wrote, “challenges the layman and the humanist to judge what the scientist is doing because it concerns all men, and this debate must of course be joined by the scientists themselves insofar as they are fellow citizens.”7 True, we allow the scientist to weigh in, but not because of their authority as experts, nor even because their research is responsible for the technologies that have prompted the question in the first place; rather, scientists are given a voice because they too are human beings and must therefore be invited to ponder questions of humanistic concern. This is a way of saying that the question about the human stature is located upstream of all scientific inquiry, prior to any theoretical decision to reach for a scientific outlook characterized by objectivity and universality.

From a scientific point of view, it could be argued that this attitude has things exactly backwards: that it is the scientist alone—and not all human beings—who is in a privileged position to make authoritative statements concerning the true nature of scientific and technological progress. Arendt gives voice to this perspective this way:

For the point of the matter is, of course, that modern science—no matter what its origins and original goals—has changed and reconstructed the world we live in so radically that it could be argued that the layman and the humanist, still trusting their common sense and communicating in everyday language, are out of touch with reality; that they understand only what appears but not what is behind appearances [...]; and that their questions and anxieties are simply caused by ignorance and therefore are irrelevant.8

Indeed, it is precisely this attitude which has a great deal of traditional philosophical support behind it: technocratic rule has always rested on the idea that complicated circumstances require specialized knowledge to understand and deal with them. The modern world, with its immense techno-industrial systems, makes a singularly strong case for expertise, because whatever it is that the humanist knows about is more irrelevant than ever to the complicated realities of public, political—and, indeed, human—life.

But Arendt argues that this modern scientific and technocratic perspective can never mark a definitive escape from the more original human perspective on things: it is a garment we put on, so to speak, that can never become a wholly new skin. We carry the human vantage with us wherever we go, and run the danger of incoherence whenever we attempt to dispense with it entirely. Arendt writes:

The scientist has not only left behind the layman with his limited understanding; he has left behind a part of himself and his own power of understanding, which is still human understanding, when he goes to work in the laboratory and begins to communicate in mathematical language.9

It is to this human element—the part of oneself that we implicitly renounce whenever we pursue modern scientific questions in a mathematical language—that the question about the human stature is addressed. There is something self-defeating, in other words, about the scientific attempt to conceive—and even to physically reach—the universe as it exists in itself, purged of all anthropomorphic and therefore unscientific elements. Indeed, the more ardently we wish in the literal sense to take up the universal perspective of scientific theory by venturing out into space, the more thoroughly we must surround ourselves in practice with technological contrivances of our own making: not for nothing is the clearest illustration of this peculiar principle none other than the astronaut, whose perspective on the universe is liberated from the anthropomorphic constraints that characterize life on earth, but at the cost of having to remain totally enveloped in a cocoon of human design, on pain of instant death.10

In general, I think we can also say that this principle is broadly true of any form of thinking that we might describe as “ideological”: these attempts on the part of situated and limited human beings to achieve an absolute perspective that transcends any basis in the tangible experiences of history and fact frequently break down in spectacular and unexpected ways. The spirit of modern science has tended not only towards a certain theoretical incoherence—the “absurdity” of nature, as Richard Feynman called it—but it also harbors the great practical difficulty that the study of nature in all its purity must be pursued with the aid of highly contrived and artificial technologies of ever-greater complexity. At the very least, we must remember that what is most remarkable about the ability of modern science to step outside of our inherent anthropomorphic limitations, to the extent that it succeeds in doing so, is that it is we human beings ourselves who have designed and effected this liberation in the first place.11

In the twentieth century, there was a great deal of talk—especially pertaining to the risks posed by nuclear weapons—about a glaring mismatch between our technical competence and our share of social and political insight on which we might draw to steer it. Whatever power this worry ever had to check the campaign of perpetual technological innovation has largely been overwhelmed by the geopolitical and market imperatives that incentivize ever-more far-reaching technological transformations. But for Arendt, the problem isn’t the oft-mentioned lag in our moral or political judgment as it struggles to keep up with the forward march of techno-science—it’s that, as she puts it, “man can do, and successfully do, what he cannot comprehend and cannot express in everyday human language.”12 That is to say, modern science simply isn’t rooted in a perspective that has any particular concern for the world in which human affairs are conducted, and before modern science has really gotten underway—and long before its most unlikely and even incomprehensible discoveries have been made—it has already taken leave of what are, from its own perspective, mere human prejudices. And ultimately, for Arendt, the technologies that are constructed on the basis of scientific theory are, in all their foreignness, thrust right back into the center of everyday life.

By a similar maneuver, we might say, the algorithmic language that is employed, not to study the universe but to manage human experience and behavior on earth, shares a similar set of ideological commitments that look down, as it were, on human life from an external and allegedly “higher” perspective. And so, too, the theoretical underpinnings of AI rest on a kind of “dehumanization” of the concept of intelligence itself, in which it is divorced from the intelligent qualities of the human mind on which the concept of intelligence is historically based. It is this separation that makes it plausible in the first place for intelligence not only to be mimicked by machines, but also maximized beyond the bounds imposed by nature upon human cognition. These algorithms and artificial intelligences, which begin as philosophical abstractions, conclude with the reintroduction of politically and socially potent technologies back into the sphere of human experience.

Arguments that urge us to wed technical expertise to humanistic learning—by educating future technologists in ethics, law and philosophy, say—miss something deeper, something that Hannah Arendt saw: that modern science and the technologies to which it gives rise have removed themselves from human concerns at their very outset. Taken strictly on its own terms, science neither promotes nor opposes such human values as the flourishing of human beings, the survival of organic life, or even the continued existence of the Earth itself. Hoping to graft these exogenous humanistic values onto scientific research and technological development is to expect that haphazardly conjoining two differing intellectual standpoints will spontaneously give rise to a conciliatory relationship that promotes both human values and scientific discovery—rather than to expect the perpetual antagonism that would seem rather inevitable. If the scientific standpoint will be opposed on the level of theory, it will have to be on its own terms, and not from the point of view of a political or social critique to which it owes no deference.

The level of practice is another story. During this past year, I’ve been turning over in my mind something of a maxim for addressing our implicit assumptions about the authority of certain scientific and technical experts over ways of understanding the world that rest on a more primary contact with reality. It has worked itself into the following simple form: Make peace with the wisdom of your own inexpert assessment of things. I propose, in other words, that we make a virtue out of a skeptical attitude towards the idea that human events must be guided solely by the specialized knowledge of technical experts. True, it would be better if these experts were more educated in human questions than they typically are, but to my mind the problem has less to do with what experts don’t know than with the fact that their authority is seen to come exclusively from what they do know. I am not here raising the flag of a mindless technophobia, nor espousing a reactionary know-nothingism; I mean only to point out the fact that scientific and technical knowledge, whatever marvelous powers they offer us, do not stem from our original capacity to see and interpret the world, but from a set of historically-contingent theoretical abstractions. Trust the relevance of your standpoint within the public discourse about technology, not because you possess the right knowledge or sufficient information to render you an expert, but because you draw upon the only possible perspective from which political judgments can be made at all—one rooted in the primary human experiences that precede abstraction and ideology.

Most notably, as Sam Altman, CEO of OpenAI—which began as a nonprofit aimed at mitigating the risks posed by AI before transitioning to a for-profit company in 2019—told the U.S. Senate last May: “If this technology goes wrong, it can go quite wrong.”

The appearance of technocracy in Western political philosophy can arguably be pinpointed with some specificity in the allegory of the Ship of State given by Socrates in Plato’s Republic, 487e-489e. Here, we find the skill required for political rule compared with the skill of piloting a ship: both roles require extensive knowledge and experience which, when acquired, gives one the right to claim authority.

There is memorable (and funny) moment in Plato’s Gorgias, where the dialogue’s titular character is challenged by Socrates to explain how practitioners of the art of rhetoric have “no need to know the truth about things but merely to discover a technique of persuasion so as to appear among the ignorant to have more knowledge than the expert”. To this Gorgias replies: “But is not this a great comfort, Socrates, to be able without learning any other arts but this one to prove in no way inferior to the specialists?” (Gorgias, 459b-c). The point, of course, is that the comfort offered by the singular art of rhetoric resides in the fact that it can help you speak with seeming authority on any imaginable subject without having any real knowledge outside of the rhetorical art itself.

Aristotle, Nicomachean Ethics, VI, ch. 7. 1141a22, (italics mine)

Lorraine Daston and Peter Galison, Objectivity, pg. 17.

Erwin Schrödinger, Science and Humanism: Physics in Our Time, pg. 25, (italics mine).

The quote is from Feynman’s book QED: The Strange Theory of Light and Matter, pg. 10. I am indebted in this paragraph to a recent article in American Affairs by Edward R. Dougherty, which can be found here.

Arendt, Between Past and Future, pg. 262, (italics mine).

Ibid., pg. 262-3.

Ibid., pg. 263, (Italics mine).

Ibid., pg. 272.

“Max Planck was right”, Arendt writes, “and the miracle of modern science is indeed that this science could be purged “of all anthropomorphic elements” because the purging was done by men.” Between Past and Future, pg. 263, (italics mine).

Ibid., pg. 264.