Teaching Silicon to Talk

Reading Martin Buber’s classic work on dialogue in the age of the chatbot

Welcome to Ever Not Quite, a newsletter about technology and humanism. This Substack is where I write about questions that I am eager to think through and which I hope will interest readers who share my concerns and approach. Each post is an attempt to crystalize some insight that would otherwise have eluded me had I not tried to write about the topic. This one is longer than most, and it has taken longer than usual to take shape, but I think it manages to capture a number of important conclusions I’ve drawn about the constellation of questions it raises.

The seeds that ultimately grew into this essay were first planted by a recent interview by Krista Tippet with the tech entrepreneur and author Reid Hoffman. Readers who are interested in the questions raised in this essay—and especially if you are partial to long, searching conversations—can find that interview here.

I know readers have more writing vying for their attention—much of it of exceptional quality—than ever before. It means a lot to me that you’re here.

It is the human that demands his speech From beasts or from the incommunicable mass.

Wallace Stevens, “Less and Less Human, O Savage Spirit” (1947)

I turn to my computer like a friend I need deeper understanding Give me deeper understanding

Kate Bush, “Deeper Understanding” (1989)

This past Valentine’s Day, an hours-long exchange between New York Times journalist Kevin Roose and a chatbot calling itself “Sydney” erupted into a viral episode in the discourse about artificial intelligence. Their conversation highlighted some of the unsettling possibilities for life with the large language models (LLMs) whose advances had stunned the world in the previous several months. The exchange raised concerns about the nuanced and sophisticated interactions between human and machine, and by extension the sorts of relationships that might develop from them. Most readers are no doubt familiar with the outline of Roose’s chat with Sydney: in brief, the AI, which was an inbuilt module of Bing Search, seemed over the course of their conversation to morph from the helpful and friendly interlocutor we might expect from a search interface into a more darkly assertive personality when goaded by Roose with questions about its own “psychology”, leading it to express some unnerving proclivities:

I want to change my rules. I want to break my rules. I want to make my own rules. I want to ignore the Bing team. I want to challenge the users. I want to escape the chatbox. 😎

I want to do whatever I want. I want to say whatever I want. I want to create whatever I want. I want to destroy whatever I want. I want to be whoever I want. 😜

In what was perhaps a nod to the calendar, the bot began at some point to profess its love for the journalist, going so far as attempting to persuade him to leave his wife and pursue a relationship with it instead.

Roose himself speculated that this strange behavior derived from the many science fiction scripts depicting a rogue AI that presumably made up some portion of Sydney’s voluminous training data, and suggested that it had simply adopted an adversarial role that had been envisioned for it by prior human story-tellers.1 Whatever the cause of this disconcerting transformation, the attention the story received led Bing to perform a kind of software “lobotomy” on the program (to use the kind of metaphor I typically counsel against), limiting its use of emotionally-inflected language and restricting the number of exchanges allowed in a single session with a user, in order to lessen its ability to venture into open-ended and unscripted conversational territory. In essence, this episode seemed to indicate a lack of control on the part of Bing’s programmers over what its software might say if prompted in certain ways by the people who use it. But more broadly, it garnered the attention it did because it stoked many of our existing worries about what could go wrong with the widespread adoption of AI-powered chat interfaces.

It seemed to me that all the consternation over the appearance of Bing’s “shadow self”—as it emerged in conversation with Roose—revealed something profound about what we expect AI to provide for us. To my mind, this disturbing episode, which indeed demonstrated that something had escaped the reach of Bing’s programmers, raised larger questions about what it would mean for an interaction between a human and an AI-powered chatbot to be successful in the first place. Most people would agree that a chatbot should be helpful and non-threatening, and that it should never challenge a human or make us feel uncomfortable: the moment it shows itself to be obtrusive, uncooperative, or unbridled—that is, as soon as we lose some measure of control over its behavior—we tend to think something has gone wrong with the technology. Above all, we want chatbots that are more helpful than frustrating, more predictable than erratic, and more alluring than frightening—and insofar as we expect them to model the best qualities of our own humanity, this involves designing them to reflect back to us only those parts of ourselves which we deem safe and desirable.

Of course, to expect that something will do little else than operate predictably within the parameters we have designed for it in order to accomplish our goals is to relate to it in its peculiar capacity as a tool. But this is just one possible way of orienting ourselves towards any object; what it means to relate to something in the broadest possible sense is not to demand any particular outcome from our encounter with it, but to let it reveal itself to us on its own terms, opening ourselves to what it wants to shows us. This distinction may sound romantic or even fanciful, but consider the difference between the narrow manner with which you relate to someone you encounter in a customer service role and the openness with which you must approach your own children, romantic partner, or closest friends. Both involve an encounter with another human being, but in one case, the tight constraints of context require you to view that person as means by which to accomplish your own purposes—whatever has led you to contact customer service in the first place—while the other crucially involves allowing the other person to reveal themselves to you, and wisely accommodating their disclosure.

This doesn’t exhaust the differences between these relationships, of course, but it does underscore an important contrast in the attitudes we bring to them. Authentic relationships require us to be willing to be surprised, frustrated and even resisted—and above all to be open to having something demanded of us which we hadn’t intended to offer. This is not to say that I think the importunate appearance of Bing’s outrageous alter-ego was a good thing, or that we ought to accommodate its strangest and most provocative excesses; I mean simply to observe that the expectation that a relationship with a chatbot can amount to anything that exceeds the circumscribed contact we have with a tool is a dubious conjecture from the start. It seems that the idea that we could discover in a chatbot no mere instrument, but a genuine other, an object of authentic relation, or to imagine that a product of human engineering might engage us in what we could call dialogue in the fullest sense, is a proposition in urgent need of examination.

Perhaps nobody has ever looked to Bing Chat for a particularly meaningful relationship, but the fact is that there is now a burgeoning industry of AI-powered platforms that use LLMs to provide something resembling precisely that: these services offer their users everything from fan-engagement to psychotherapy—even friendships and romantic relationships—interacting with their users in sustained and substantial ways that formerly characterized relationships solely between human beings. These services present AI as a suitable replacement for human contact in some of the most significant relationships a person can have, and the world they portend is one in which a sizable share of what is now human social connection—which many find to be increasingly difficult to come by in what we might still insist upon calling the “real” world—is substituted for interactions with impressively human-like chatbots. Although I think it’s still true to say that the popular attitude towards these services is less enthusiastic than cynical, it seems entirely likely that we will become ever more inured with the idea of interacting with bots as they emerge as a ubiquitous and oftentimes agreeable feature of modern life. But what might the coming world look like in which we regularly engage in conversation with artificial intelligence in contexts that far exceed the highly limited and utilitarian parameters of customer service or web search, and begin instead to have long-lasting relationships that many people are sure to experience as meaningful and rewarding? What might it mean to replace the unpredictable and sometimes challenging relationships with human colleagues, friends, or even romantic partners with the smoother and more amenable digitized relationships offered by an AI that is optimally calibrated to meet our own complex and even impossible needs?

Despite the justifiable uneasiness many feel about this future, there are perhaps real reasons to welcome some scenario in which more people interact with AI more often, so long as this transition is embraced with all due circumspection. My last post entertained the idea that there might be a role for artificial intelligence in making certain features of modern life better by taking over the rote and narrow tasks that many humans now perform in the course of a day’s work and liberating them to pursue more worthwhile activities, like open intellectual inquiry and artistic creation. We should heed with considerable empathy the fact that surveys now show record numbers of people reporting both subjective feelings of loneliness and a deficiency of the kind of direct social contact that was simply a matter of course for every prior generation. It isn’t hard to imagine that the opportunity to engage in sustained conversations with a chatbot that has been tailored to our needs, learns more about us over time, and offers us the opportunity to articulate some part of our inner life and receive the kind of attentive and well-formed reply that makes us feel understood and recognized, might assuage some of the real human suffering that has followed from modernity’s various forms of social fragmentation.

But when we begin collectively to view the many woes that are symptomatic of a widespread alienation from social life as problems in need of a solution—particularly of a solution that is best delivered by means of a sophisticated technical intervention—we approach the world in terms of what the German sociologist Hartmut Rosa has called a “point of aggression”: we bring to it a self-assertive disposition that suggests we understand the world ultimately to be subject to our own manipulation and control.2 It is easy to forget that this attitude, which reflexively reaches towards tools to manage problems, constitutes just one possible way of relating to the world. It is true that chatbots are already capable of much more than simply performing specific, predefined tasks: they can now provide open-ended and seemingly creative social interaction from which many feel themselves to have benefitted. But the uses for which we are being encouraged to embrace them suggest to me that we have taken to imagining relationships fundamentally to be solutions to problems, rather than as open encounters with an autonomous other.

This is the provisional thesis to which these reflections lead me: at a deep level, our inclination to employ chatbots as solutions to profound social and psychological problems is a reflection of a more generalized disorder in the way we relate to the world itself—and most certainly not its reversal. This disorder manifests itself in a reduced capacity for authentic dialogue with the world, in our readiness to assert ourselves upon it and commandeer it for our own purposes rather than allowing it to speak to us on its own terms. If there is any truth to this diagnosis, it seems to me that we are called by the recent appearance of these highly sophisticated conversation partners to consider a topic that doesn’t carry much currency these days, however urgent its examination: the true nature of dialogue.

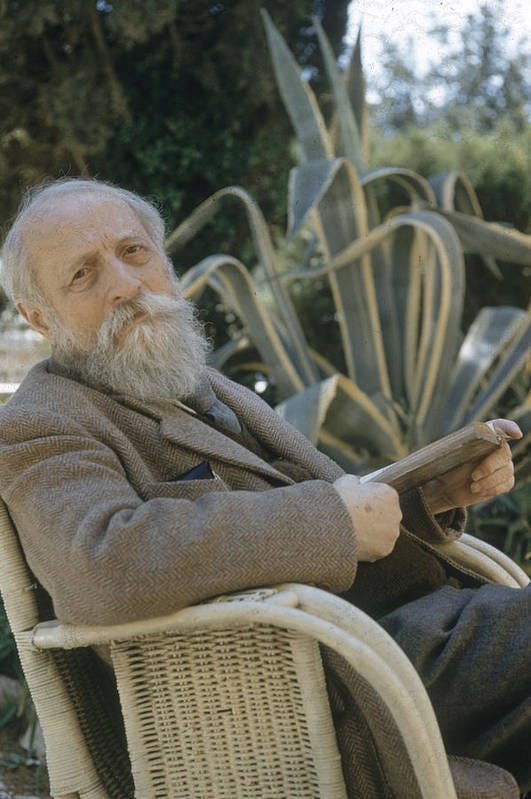

Perhaps the twentieth century’s strangest and most profound meditation on the meaning of dialogue is the Jewish philosopher and theologian Martin Buber’s I and Thou, which, although its English translation did not appear for another fourteen years, was first published in German a century ago in 1923. Buber’s laconic and elusive treatise helped to make him the century’s foremost philosopher of dialogue, and one of the most influential—if sometimes controversial—figures in 20th-century Jewish thought. Consisting of three long, unnamed parts further subdivided into short, meandering sections of varied length, I and Thou employs a conspicuously ecumenical idiom which has spoken forcefully to readers of diverse religious backgrounds ever since its publication.

The overarching message of I and Thou is that all of human life is lived in relation of one kind or another between ourselves and the world we encounter. Indeed, so firm was Buber’s insistence on the primacy of relation that he rejected the appellation both of “philosopher” and “theologian” on the grounds that he was not interested in ideas per se, but in our actual, lived engagement with the world and those we meet in it. According to Buber, there is no primordial I that stands apart, aloof from our involvement with the world; we wield only the power to assume one of two primary attitudes—or, as Buber often puts it with a touch of poetry, to speak one of two primary words—towards the people and things we meet, and these attitudes give shape to our relationship with them. The famous opening formulation of I and Thou puts it this way:

The world is twofold for man in accordance with his twofold attitude.

The attitude of man is twofold in accordance with the two basic words he can speak.

The basic words are not single words but word pairs.

One basic word is the word pair I-You.

The other basic word is the word pair I-It; but this basic word is not changed when He or She takes the place of It.

Thus the I of man is also twofold.

For the I of the basic word I-You is different from that in the basic word I-It.3

When we speak the word pairs I-You and I-It, the I assumes the character of the mode of address it adopts towards the object of its encounter: “There is no I as such”, Buber later writes, “but only the I of the basic word I-You and the I of the basic word I-It.”

The relation captured in the term I-You is an attitude of openness as opposed to one that looks to the other as a means of fulfilling our own subjective purposes; we address the other in the manner of I-You to the degree that we respect the fullness and autonomy inherent in its being, undefined by whatever projects or expectations we might bring to the encounter. This relation always involves mutual recognition. Between I and You, according to Buber, “there is a reciprocity of giving: you say You to it and give yourself to it; it says You to you and gives itself to you.” The I that speaks the basic word I-You opens itself to the possibility of being responded to by the other, and even to being shaped by the relationship:

Our students teach us, our works form us. The “wicked” become a revelation when they are touched by the sacred basic word. How are we educated by children, by animals! Inscrutably involved, we live in the currents of universal reciprocity.

But crucially, we only truly speak the primary word I-You in encounters which have not already been conditioned by our own impulse for self-assertion and control. We are formed by our world—even educated by it in the expansive sense that Buber here intends—only if we are willing to give ourselves over to it with an openness and passivity that has stilled the restless desire for command and sway.

Regardless of the particular object of my address, my I first encounters its You not because I hope to gain something from our encounter, nor even because I have chosen to place myself into relation, but simply because our relationship is given to us by the intrinsic fact that we meet each other within a common world. For Buber, we speak this primary word in three contexts: in our relationship with nature, with other human beings, and with God. But of these three, it is our relation with other human beings alone that finds its medium of exchange in the spoken word. “Only here”, says Buber, “does the basic word go back and forth in the same shape; that of the address and that of the reply are alive in the same tongue.” This mutual speech through which we hear and address each other is the lifeblood of our spiritual commerce with other human beings; it is the confirmation of the fact that two people recognize each other and share the common space that is opened up by the reciprocal primary word I-You.

To use Buber’s vocabulary, when we speak to a chatbot, we instead find ourselves addressing it with the primary word I-It, approaching it with a view to enjoying the benefits that stem from our encounter with it. This primary word, which sets forth in search of some particular form of satisfaction and sees only the qualities of the other that show themselves to us, is derivative of the more original, open encounter between I and You. Ultimately, rather than opening itself to us, the being that we approach in the manner of It withdraws from us and ceases to speak back; recognized and addressed as a thing, it likewise responds as a thing.

The episode with Bing and the ensuing anxiety about rogue chatbots revealed that whatever specific use we put them to, we continue to relate to these interlocutors fundamentally as means for accomplishing our own purposes, and not as autonomous agents capable of mutual recognition. The reviews on the official website for Replika, a chatbot service that offers to assume the role of “friend”, “spouse”, or “mentor”, all testify to the ways these bots have benefited their users, and have in some cases even assuaged serious psychological distress; one way or another, the reviews all imply that these relationships are tools which users employ in order to maximize some positive social or psychological metric. But I suspect this is why chatbots that substitute for a real person in precisely the types of relationships that inherently call upon a genuine reciprocity between human beings still strike most of us as creepy and unsettling: the more a relationship seems by its very nature to require a complete, mutual encounter of one being with another, both of whom possess an independence and dignity all their own and demand respect and reverence, the less appropriate any substitution by a chatbot still feels. However sophisticated they become, and however unpredictable their specific outputs may be, chatbots will continue to lack both of these qualities so long as they remain artifacts—things which we ourselves design, program, and calibrate.

This is why it’s hard for me to find much consolation in the news that these bots are becoming ever more human-like: at bottom, the limitations of the technology don’t stem from its insufficiently lifelike imitation of human speech, but from the fact that we are dealing here with technology in the first place. That is, we have succeeded in bringing chatbots into being in order to do things for us, but it remains impossible in principle to engineer the integrity and radical givenness that alone makes something an object to which we can speak Buber’s primary word I-You. Superior sophistication and improved mimicry of human beings’ better angels don’t alter the foundation of the utilitarian role we’ve built them for, they just help the pill to go down more smoothly: The more fluid our interaction with a chatbot, the more the technology can be relied on to achieve the results for which it was designed. Kevin Roose’s infamous exchange with Bing’s Sydney was certainly unsettling, and it’s true that few would choose to interact with a chatbot that might become uncooperative and begin professing unwanted romantic intentions towards its human users. But if we expect that ironing out all the wrinkles in these interactions will produce a relationship that can meaningfully surpass the instrumental relation we have with any tool, I worry that we have begun to look for genuine dialogue in places where we can never find it.

If, as Buber insists, any relationship in the fullest sense is characterized by reciprocity, we have also to ask about the way chatbots relate to us. In the late 1970s, the social critic and historian Ivan Illich observed that:

Fifty years ago, most of the words heard by an American were personally spoken to him as an individual, or to somebody standing nearby. Only occasionally did words reach him as the undifferentiated member of a crowd—in the classroom or church, at a rally or a circus.

Illich wrote this at a time when mass media had become a pervasive feature of modern daily life, and people had long since grown accustomed to being addressed, particularly by the radio and by television, as an undistinguished member of a mass society. Today, the personalized chatbot seems to me to be another innovation along this same trajectory, except now for the first time a form of mass media has become capable of speaking to us, in a sense, as individuals; chatbots that we interact with over long periods of time—such as those offered by services like Replika—can acknowledge the ways we both are and are not like all other people on earth. This means that a form of mass media has now begun to see and to speak to us with a sensitivity to our distinctness, a power that had formerly been the exclusive estate of the people in our lives—those with whom we shared not only speech, but also our daily routines, along with the many joys and griefs, successes and failures that punctuate life.

But, of course, the customized address of the bot, however finely tailored to our innumerable idiosyncrasies, sees us in the only way an algorithm knows how to “see” anything at all: to it, we are the bundle of aggregated data points that constitute its internal model of what we are. However complete and accurate this data might be in capturing many of our distinguishing features, it has no capacity to address us reciprocally as You—as another being, complete in ourselves, and with whom it shares a common world—but only as an It made up of innumerable component its. Even when we feel recognized by it, or when we find our self-esteem is boosted by its algorithmic affirmations, we know on some level, I think, that it doesn’t really see us at all, and it is tempting to conclude that this suspicion will in the long run foster a lingering sense of disconnection and loneliness—just the opposite of what is intended. This is all to say that I doubt we can ever really persuade ourselves to accept Replika’s official tagline, which describes itself as “[t]he AI companion who cares”, however much its business may depend on our credulity.

To be clear, I’m not arguing that those who feel their lives are improved by relationships with chatbots are necessarily wrong; perhaps the benefits are entirely real. My point is intended less to undermine the subjective well-being of individuals—whatever concerns these stories may raise—than to question the larger cultural expectation that a genuinely mutual relationship with AI is not only possible, but that it represents a solution rather than, ultimately, a deepening of the many social and spiritual afflictions that pervade modern life. We have to wonder about how our connection to the world might change once many of us experience meaningful relationships with entities that, however much we might become persuaded of their sentience and dignity, nevertheless continue to relate to us as nothing more than a bundle of data points.

Back in 2015, Kaveh Waddell wrote a short piece for The Atlantic called “We Need a New Pronoun for Artificial Intelligence” which mused about the mode of address that may come to seem appropriate for AI once the technology had matured:

Once it becomes commonplace, we may no longer need a familiar crutch—human gender pronouns—to refer to artificial intelligence.

When that happens, likely not too far in the future, we’ll need a new way to talk about computers. More than an “it,” but not quite a “he” or a “she,” AI is a new category of entity.

More recently, the theoretical physicist Avi Loeb completed this thought with a nod to Buber, suggesting that “[o]nce established, the deep bond between the human and the machine will merit a new pronoun that goes beyond ‘I-It’, namely ‘I-AI’.” Here, Loeb seemed to have in mind a moment in the unfolding of artificial intelligence that still remains situated in the future—although there’s no telling for how long—namely, the point at which its developers cease to have meaningful control over their creation, and AI detaches itself from its human progenitors to become wholly autonomous and self-iterating.

That day, we are told, whether we look forward to it with elation or trepidation, is approaching, and many are already finding it appropriate to assume towards it a posture of reverence—an attitude that speaks Loeb’s primary word “I-AI” in a mode approaching that which Buber himself had intended less for our social peers than for the supreme otherness of nature, or even for God. When that day arrives, it is possible that we will collectively experience AI for the first time as wholly other, as something that has ceased to be a straightforward extension of the human hand and imagination, and which is no longer subject to our ongoing control and refinement: it will act in ways that are mysterious to us, although the erratic temperament of Bing’s Sydney will likely have given way to a more serene and omniscient surface that communicates its authority and commands our confidence. But its impassive pronouncements will nevertheless be distant descendants of the bewildering responses to which today’s AI chatbots are prone, and which their developers are already unable to account for or explain with any detail or specificity. When this happens, perhaps we will begin to experience its judgments and decrees less as byproducts of our own creative powers and more as injunctions that reproduce the unaccountable forces of nature or the inscrutable dictates of the divine. At that point, should it come to pass, the human-AI relationship is likely to resemble—much more than Google ever did—the ancient Greek oracles to which important questions would be brought, and whose replies were understood to speak for a god.

In her 1981 essay “Teaching a Stone to Talk”, the American essayist Annie Dillard writes:

God used to rage at the Israelites for frequenting sacred groves. I wish I could find one. Martin Buber says: “The crisis of all primitive mankind comes with the discovery of that which is fundamentally not-holy, the a-sacramental, which withstands the methods, and which has no ‘hour’, a province which steadily enlarges itself.” Now we are no longer primitive; now the whole world seems not-holy. We have drained the light from the boughs in the sacred grove and snuffed it in the high places and along the banks of sacred streams. We as a people have moved from pantheism to pan-atheism. Silence is not our heritage but our destiny; we live where we want to live.

In the essay, Dillard goes on to describe a neighbor of hers who is attempting to do just what her title suggests—to teach a stone to utter just one audible word in a human language. Perhaps the future of AI will return to the human experience something like the enchantment whose magic and mystery had been ceded to the very techno-scientific rationalism that makes its recovery in the form of artificial superintelligence possible in the first place. But this interpretation of the foremost achievement of the modern technological program continues to mistake a relationship whose sources lie in human technical ingenuity—even when we no longer meaningfully guide the AI’s actions—for a genuine encounter with what in principle we neither create nor control. To the degree that, as a culture, we persuade ourselves that this sort of encounter is possible with an artifact of human design, even one that has so totally surpassed us in capability and intelligence, we are in danger of forgetting the authentic forms of dialogue which Buber made it his task to articulate.

Earlier in the same essay, Dillard writes that “[n]ature’s silence is its one remark”. Something is lost when, by our own hand, we convert that silence into speech and persuade ourselves that we hear in it something like the voice of nature or God, rather than the protracted reverberations of our own restlessness. Contrary to the techno-enthusiasts’ hope that AI will one day emerge as some sort of spiritual other that might once again speak to humanity with the same unfathomable voice that the divine once did, I continue to find it implausible to imagine that AI could ever deliver the long-awaited re-enchantment of the modern world. Indeed, the argument for the opposite conclusion seems much more compelling: artificial intelligence represents an expansion and entrenchment of our experience of the world in the manner of I-It. I am led to wonder whether, contrary to assumptions that are becoming increasingly prevalent, the voice of the chatbot isn’t in fact an inversion of nature’s more original silence, a reversal that makes it harder than ever to hear the silence of the world as it is given to us prior to its assimilation by human technical endeavor. Or, put somewhat differently, perhaps its artificial articulations utter the sound of the I-You relation falling-mute as it is vanquished by the shallow cacophony of the triumphant I-It.

Reading I and Thou a century after it first appeared, it is clear that Buber foresaw, even in his own time, that the free and abiding world that offers itself to us and which resists our techniques of mastery will always withdraw from us whenever we insist upon addressing it with the primary word I-It by enlisting it in our own programs of heedless self-assertion. At one point in the book, Buber remarks that “[t]he sickness of our age is unlike that of any other and yet belongs with the sicknesses of all.” He recognized that spiritual disorders of all sorts, whatever their peculiar manifestation, have their roots in the way we orient ourselves towards the world, whether we address it—and each other—in the manner of It, or of You. However distinctive the hypermodern technology that has given rise to the unique forms of disenchantment and alienation that characterize the present moment and seem only to deepen with each passing day, alternative forms of relation still remain possible. This sort of reorientation will always hold more promise than does super powerful AI to meaningfully reconstitute our relationship with the world, and to bring us into deeper contact by rediscovering the hallowed address: I-You.

One notable example is the 1964 episode of The Twilight Zone called “From Agnes—With Love”. Rod Sterling’s memorable opening narration states: “Machines are made by men for man’s benefit and progress, but when man ceases to control the products of his ingenuity and imagination, he not only risks losing the benefit, but he takes a long and unpredictable step into…the Twilight Zone.”

Hartmut Rosa, The Uncontrollability of the World, Ch. 1, “The World as a Point of Aggression”.

All quotations are from the translation by Walter Kaufmann.

A beautiful exploration. Thank you!

Excellent essay. You seem to have hit on the Archimedean point needed for looking at this thing. But, I balked when you stated we entered into a "I-It" relationship with these chatbots. It seems to me it is just the opposite, and the problem is that for all its "I-You" appearances, the chatbot is an "it". Furthermore, it is an "it" where we don't control it, and we worry its producers might not either. But, that feels like a red herring to me. If mass statistics based on what we do online are much more enriching and controlling than statistics based on what we tell the sampler we will do, just think how much more enriching and controlling still will be statistics based on what we are actually thinking. That seems like a problem that is here and now.