Welcome to Ever Not Quite—essays about technology and humanism.

This essay attempts to name something for which—or so it seems to me—we have lacked a satisfactory term. I have argued before against the reasoning which attempts to defend human preeminence by insisting that “no technology could ever do ‘X’”, however sophisticated or impressive the ‘X’ in question might be. This, it seems to me, is a weak position from which to secure humanistic values, for reasons which I’ll explain below. Here, I offer an alternative basis on which to think about what distinguishes us from even the most powerful simulations of human competencies. I am calling this the “anthropological aura”.

These reflections, of course, don’t exhaust all we might wish to say about what is at stake in the present unfolding of artificial intelligence, but I hope they provide a helpful category which may perhaps be of some use in your own thinking about these issues.

I have uploaded the audio recording to an RSS feed, so you should be able to find it in your preferred podcatcher.

As always, thank you for reading. If you’d like to support my work, consider becoming a paid subscriber and/or sharing this essay around within your circles.

“To perceive the aura of an object we look at means to invest it with the ability to look at us in return.” Walter Benjamin, “On Some Motifs in Baudelaire”

In a widely-read essay from last fall, Dario Amodei, the CEO of the AI company Anthropic, ventured that something approaching artificial general intelligence (AGI) “could come as early as 2026”.1 There was nothing particularly novel in this prediction; if you go looking, you can find many such prognostications from prominent observers anticipating our imminent passage beyond this technological event horizon. They have their critics, of course (see

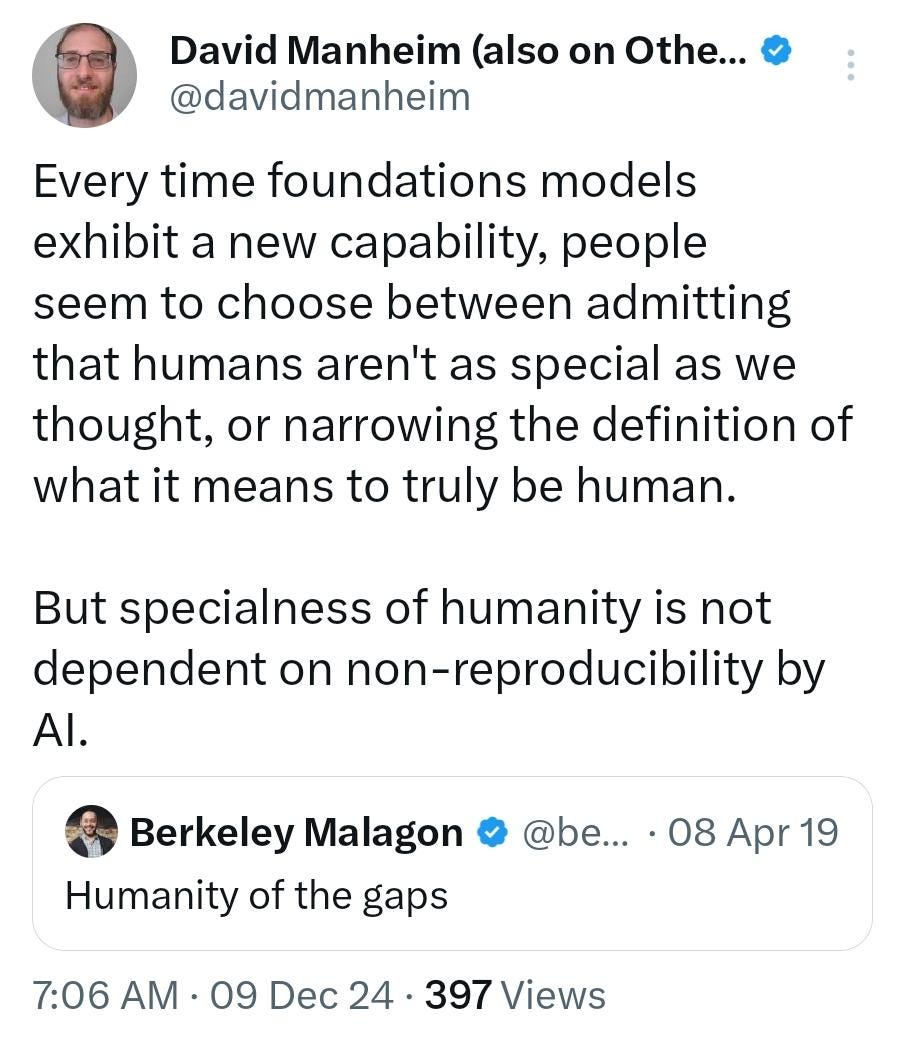

), but in an important sense, the precise timeline matters little so long as, in principle, such a thing could ever be achieved.2Last spring, I wrote a long essay about what is sometimes called the “humanity of the gaps”: an inclination among some skeptics of technology to locate the quintessential human quality in whatever it is that no machine can yet do. What makes us special in a world of large language models, for instance, is that the best human writers can still write better than even the most advanced algorithms. You find this sort of argument all over, and there are several problems with it. Chief among them is that it unwittingly places our sense of ourselves at the feet of the historical contingencies which underlie the development of technology.

The term “humanity of the gaps” is an adaptation of the nineteenth century concept of the “God of the gaps”, which, during a period of intense scientific advancement, concluded that the work of God is witnessed in whatever it is that science cannot yet explain, all else having been understood in terms of the blind operation of mechanical processes. Whatever modern science can account for, it is assumed, requires no recourse to the explanatory power that might be supplied by divine intervention; conversely, whatever science cannot account for must therefore suggest some inscrutable recess in the texture of nature in which God has taken up residence. What was once seen as a vast “theater of God’s glory” is thus made to contract to the scale of those isolated phenomena for which science continues to lack a satisfactory account. In much the same way, then, the “humanity of the gaps” holds that whatever makes human beings unique amidst increasingly capable machines must reside only in what we can do which nothing else yet can.

The temptation of these consolations is understandable, but I think ultimately mistaken and unhelpful. The trouble is that these “gaps” arguments assume that God and human beings alike owe their justification only to the failure of the techno-scientific endeavor, requiring continued scientific ignorance and technological incompetence in order for God and humanity to have any meaningful place in the world. These arguments, which are so often made by would-be defenders of theological and humanistic values, underestimate science and technology and inadvertently cede power to the scientists and engineers whose successes they authorize implicitly to set God and humanity into retreat.

In his seminal 1935 essay “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”, the German philosopher and literary critic Walter Benjamin developed one of the concepts for which he is best known today. What Benjamin calls the “aura” of an artwork names what can never be reproduced, either by mechanical or artisanal means, because it resists by its very nature the process of reproduction whereby its features might be duplicated and exported. “Even the most perfect reproduction of a work of art”, Benjamin explains, “is lacking in one element: its presence in time and space, its unique existence at the place where it happens to be.”3 The aura of the work of art is the work’s singular and unrepeatable presence in the world, its unique status as the one and only original, distinct from all the reproductions from which its features might nonetheless be indistinguishable.

However much the contemporary image-world has become dominated by these reproductions, most of us, I think, still share some intuition that there is something importantly different about visiting, say, Pietro Perugino’s Portrait of a Young Man from 1495 where it is currently housed in Florence’s Uffizi Gallery, and viewing even the most faithful rendering of the same image. It isn’t as though the millions who travel every year, and sometimes considerable distances, to visit the world’s thousands of art museums must do so because they have no other way of seeing what all this art looks like. We are drawn not just to an artwork’s appearance, but also to the possibility of entering its presence, of becoming a part, however fleetingly, of its continuous passage through time, space, and history, and of bringing before ourselves, unmediated, the very artifact once worked by the hand of the artist.

“[T]hat which withers in the age of mechanical reproduction”, Benjamin attests, “is the aura of the work of art.”4 That is to say, our sense of the authority which belongs to its peculiar presence in the world is weakened under conditions in which technologies of mass reproduction have emphasized not its existence as a singular artifact, but rather the accessibility of its features—its colors, form, and values—which can now be reproduced at will to meet viewers wherever they happen to be. The image can now meet us, as it were, halfway—or, as is more often the case, much more than halfway, entering our space so that we don’t have to enter its own. Even by the time Benjamin wrote his essay, the ease and speed with which original artworks could be reproduced had already elevated our attachment to their features, just as it had begun to lessen our sensitivity to the unique existence belonging only to the original—if only because the ability of the original to reach its viewer is limited by the dimensions of space and time within which it is confined.

Here’s the connection I want to draw between the artwork’s withering aura under the conditions of modern media technologies and the diminishing status of the human being relative to machines: Just as a work of art is more than a bundle of features which might be reproduced by media technologies, so the human being is more than a bundle of capacities which might be imitated by algorithms. The reproduction of an artwork, no matter how perfect, is a reproduction of the features of the original, and nothing more; so, too, the algorithmic emulation of human beings, no matter how effective, is an emulation of the capabilities of human beings, and nothing more. In both cases, what must remain unduplicated is that portion of the existence of the original which, by its very nature, resists the mimicry and appropriation which can be accomplished by mechanical or algorithmic reproduction: namely, the presence of the original in the place where it is. Like a work of art, I want to suggest, we too represent a unique presence in the world which is different from and not reducible to the functions, however sophisticated, which we are able to perform.

For lack of a better term, I will call this the anthropological aura: It names the irreducible authenticity of human being-in-the-world which, I am suggesting, is analogous to the “aura”, in Benjamin’s sense, of an original artwork. Just as, when we visit a work of art in a museum, we are following an intuition that there is something distinctive about the original which is borne by none of its reproductions, when we prefer to interact with a real person instead of a chatbot, we are likewise following an intuition that there is something distinctive about human beings which is shared by no digital simulation. All else being equal, the reason we prefer to interact with a real person rather than with a perfectly competent machine5 is at least partly the same as the reason we prefer to view an original painting rather than even the most impeccable copy: only the original has the power to involve us in a genuine encounter with a singular other, and thus to make a claim upon us by addressing us from out of its unique existence as the object that it is.

Now, I want to be careful here; the word “aura” has a shallowly spiritualistic ring to it which I do not intend—to say nothing of its contemporary appropriation in the vernacular of social media. The anthropological aura is not just another term for the soul; it does not name anything other, or even more enduring than the worldly and intrinsically situated appearance of another human being. Nor is it an alternative word for consciousness, which is yet another human quality which even the most enthusiastic champions of AI generally agree modern algorithms continue to lack in any meaningful sense.6

Indeed, I find myself reaching for this novel coinage precisely because it seems to me that we lack a satisfactory term for what I am trying to sketch: the anthropological aura is not a collection of qualities or capacities which might be available to mechanical mimicry; it is, to adapt Benjamin’s definition, a name for our presence in time and space, our unique existence at the place where we happen to be—in other words, it is what must be left behind whenever an original appearance is reproduced. To speak of the anthropological aura, then, is not to name a substance, but to acknowledge a status—the status of an original as original, in the midst of innumerable copies which bear all the same features.

Although Benjamin does observe at one point that the mechanical reproduction of art is, as he says, a “process whose significance points beyond the realm of art”, the analogy which I’m developing here between a work of art in particular and human presence in general makes for an imperfect comparison.7 While the mechanical reproduction of an artwork duplicates the features of that particular work, algorithms are not typically designed to replicate the capabilities of any one individual, but rather the capabilities of human beings at large.8 But even so, at work in both cases is the same willingness to substitute one thing for another, to treat copies and the originals on which they are based as interchangeable commodities existing on one and the same ontological plane.

Here is perhaps the most controversial claim I am making. To be philosophically unsettled by the steady erosion of the superiority of human capabilities over those of machines is to be possessed by the same misapprehension which would incline us to make no distinction between a work of art and any of its reproductions: each is to conceive of things only in terms of their features—that share of their existence which is available to duplication and export—and to extract from the spatially-situated and temporarily-bound existence inhering in an original an equality and commensurability with reproductions of those same features found elsewhere. “To pry an object from its shell, to destroy its aura”, Benjamin writes, “is the mark of a perception whose “sense of the universal equality of things” has increased to such a degree that it extracts it even from a unique object by means of reproduction.”9 This is as true of the sensibility which refuses to distinguish between an artwork and one of perhaps innumerable copies as it is of that which refuses to distinguish between the facticity of authentic human presence and the lifelike operation of an anthropoid chat interface. In each case, it is to forfeit the vocabulary of the singular, unique, and inextricably local, and to replace it with one which speaks only the language of what is repeatable, generalizable, and transportable.10

If, as Benjamin will later suggest, the technology of photography, with its power to endlessly reproduce original artworks in the form of photographic reproductions, was responsible for the decline of our collective veneration of the aura of the work of art, then the rise of artificial intelligence, with its capacity to perform tasks formerly belonging only to human beings, will perhaps be implicated in a corresponding decline in the importance which we are prepared to confer upon the anthropological aura.11 But as was true in the case of works of art, this tradeoff can occur only to the degree that we decide that what is vital about human beings is our possession of certain features: our capacities for performing this or that function. In other words, our loss of status as a consequence of the increasing capabilities of machines has the power to reshape our sense of ourselves only to the extent that we accept that the anthropological aura is either without value or is altogether unreal.

None of this is to say that chatbots aren’t useful any more than it is to say that photographs don’t represent things. They are, and they do. Nor is it to suggest that there aren’t practical consequences to choosing a path in which more and more of the functions which have belonged to human beings are taken over by machines, or that the conditions which constitute life and culture will not change profoundly once we entrust algorithms to manage more of our economies, governments, and lives. It is only to suggest that conceiving of ourselves first of all according to our possession of certain capabilities was always a gambit which threatened to orient us away from a world centered around the immediate and unmediated presence of human beings and towards one answering only to an impersonal, task-oriented expediency.12

A recognition of this reality is, I suspect, what led

to write in a recent essay:There are roles we play in the lives of others that must, by their very nature, be performed by a person. In the end those roles come down to a simple declaration. I, a human being, see you, another human being. It is a declaration no machine can make.

To perceive the aura, whether of a work of art or of another person, is to invest it with a power to implicate oneself in its own passage through time and space, just as it is to allow it to become implicated in our own. It is the crossing of two threads—two independent stories, as it were—which intersect each other and share a moment of mutual encounter. This immediacy of contact between two unique presences is what media technologies—photographs and chatbots alike—must always suppress, because reproduction creates only the semblance of contact. The duplicate may indeed be technically perfect, or the algorithm entirely competent—its attributes may even surpass those of the original in scope or quantity. But multiplied or enhanced features, in their multiplicity, must always leave behind whatever is singular in the original, whether or not it continues to claim our attention, let alone anything approaching reverence.

The decisive question will be how much this distinction actually matters to us, whether we come to consider mediated reality to deserve a status equal to that of things in their irreducible givenness, or whether originals will continue to hold a kind of primacy. To the extent that we conceive of ourselves only in terms of our capacities, we really will be subject to technological displacement, because capacities just are the kinds of features which can be reproduced and exceeded; but to the extent that we distinguish between originals and their reproductions, unique manifestations and the mediated representations which duplicate them, such a substitution will continue to have the ring of the absurd—will, indeed, remain unthinkable.

Artificial general intelligence, Amodei notes, is a problematic term, but a serviceable shorthand for a system which can match or outperform any human in any cognitive task.

One thoughtful objection to the very concept of “AGI” was recently articulated by

over at The Hinternet. The piece makes an argument which is, for the most part, different from what I’m trying to say in the present essay—but one which, I think, is entirely complementary.Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”, in Illuminations, pg. 220.

Ibid., pg. 221. Italics mine.

Of course, there are some potentially sensitive interactions which formerly required that we deal with another person—doctor’s visits or surveys about sensitive topics, for example—which many would rather have with a chatbot than with a real person, and the reason for this is precisely because these are cases where the gaze of another human being is felt to be embarrassing or even oppressive to the degree that we prefer to strip the interaction down to its barest functioning, and to eliminate the anthropological aura altogether.

I’m aware that this conversation is changing by the day, and there are those who argue that consciousness of some kind, however negligible, resides even in the simplest systems. I don’t want to get bogged down in this debate here.

Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”, in Illuminations, pg. 221.

I’m referring here to algorithms which are designed simply to be able to do things. The exception to this is when AI is used to recreate an individual person, perhaps deceased, having trained it on that person’s voice or writing or other tokens which they created in life and have since left behind.

Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”, in Illuminations, pg. 223.

Or, as Benjamin says, “it substitutes a plurality of copies for a unique existence”. Walter Benjamin, “The Work of Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction”, in Illuminations, pg. 221.

Benjamin writes in his essay “On Some Motifs in Baudelaire” that “photography is decisively implicated in the phenomenon of the “decline of the aura.” Walter Benjamin, Illuminations, pg. 187.

Justin Smith-Ruiu gets close to what I’m saying here towards the end of the above-cited essay:

The other possibility we’ve considered is that AGI is not a pipe-dream, but an arbitrary “call”. This call, as I’ve already suggested, is necessarily political, and the politics implicit in it is ugly indeed. This is the politics that bulldozes everything local, everything intimate, everything singular and idiosyncratic and irreducible to statistical regularities — and tells us the only thing that is to count as human reality is what gets reflected back to us by our machines.

Do read the entire thing; it’s well worth your time.

I like where you are headed. I see parallels to a piece I wrote a while back, and would be curious to hear your take and if you see parallels yourself: https://tmfow.substack.com/p/the-human-normativity-of-ai-sentience

Part of me also makes a connection between what you are reaching for with "anthropological aura", and what I've coined the ontic, the that-ness of being, "that there is something to experience", a concept I describe in more detail e.g. here https://tmfow.substack.com/p/the-epistemic-and-the-ontic and here https://tmfow.substack.com/p/experience-and-immersion

Do you see a similar connection? If not, how do they differ to your view?

Excellent essay, thank you. It seems to me that techno-optimists are still stuck in Newtonian physics - it's as if quantum physics (already 100+ years old) had never been suggested. That's why the human brain is called a computer, and why the lie that "the brain produces consciousness" is forever being pushed as 'obviously it does' - a massaging of mass consciousness only possible by Rationality being promoted as the sum-total of human consciousness - missing out on aspects of 'aura' such as Will, Soul, Inspiration, Intuition, Imagination, Instinct - that which partly marks 'human' as distinct from 'machine' - a whole quantum-world of activity that AI with its manipulation of 0s & 1s, and/or gates, cannot reach.

What is scary is the narrative that repeats ad nauseam that humans are inferior to machines - done so by defining humans mere 'rational' computers, meat-machines - where they compare unfavourably in this straw horse set-up. And this false and dangerous narrative seems to be beginning to stick in the public mind. Soon, humans will be begging for a chip so as 'not to be left behind' - a request based on the self-belief they are 'lesser' than machines.